|

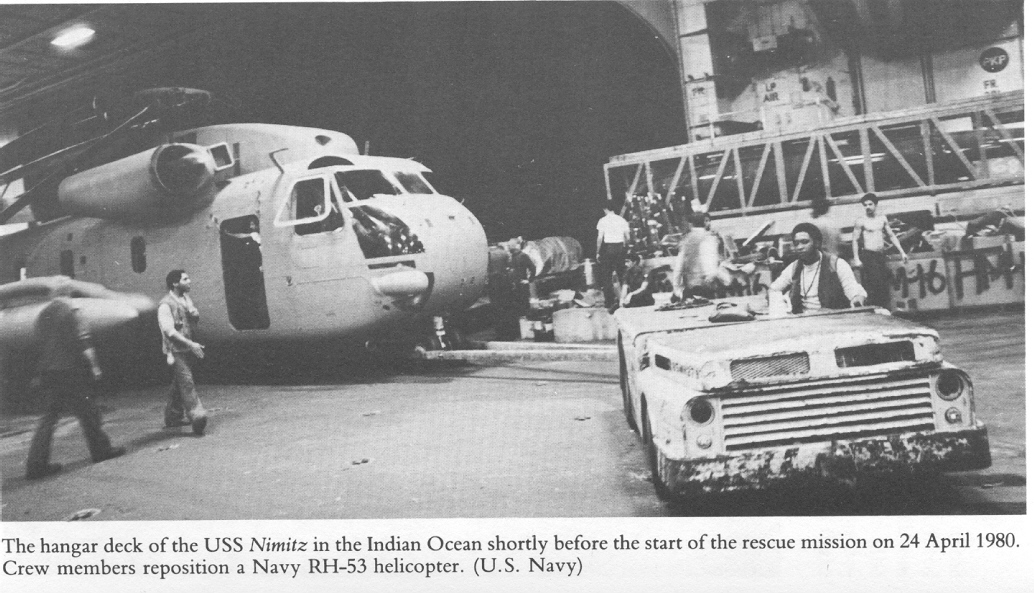

Helicopters from the USS Nimitz took off from the flight deck on April 24, 1980, with hopes to rendevous with Air Force C-130's

at a location known as Desert One. From there, they were to re-fuel, then fly to a second site known as Desert 2. After an

short stay there, they were to assault the American Embassy, and re-capture the hostages.

( RH-53s being

preflighted aboard USS Nimitz before launching on the mission where they would be stymied by dust clouds and various systems

failures. Eagle Claw was aborted when three helicopters could not complete the mission.)Air Force Association photo.

The Nimitz was in the Arabian Sea, and the helicopters had to fly over 500 miles to get to Desert One. From the Air Force

Association:

The plan was this: On the first night, six Air Force C-130s carrying 132 Delta commandos, Army

Rangers, and support personnel and the helicopter fuel would fly from the island of Masirah, off the coast of Oman, more

than 1,000 miles to Desert One, being refueled in flight from Air Force KC-135 tankers.

Eight Navy RH-53Ds

would lift off the aircraft carrier USS Nimitz, about 50 miles south of the Iranian coast, and fly more than 600 miles

to Desert One.

After refueling, the helicopters would carry the rescue force to a hideout in hills about 50

miles southeast of Tehran, then fly to a separate hiding spot nearby. The C-130s would return to Masirah, being refueled

in flight again.

The next night, Delta would be driven to the embassy in vehicles obtained by the agents. A

team of Rangers would go to rescue the three Americans held in the foreign ministry.

As the ground units were

freeing the hostages, the helicopters would fly from their hiding spot to the embassy and the foreign ministry.

Three Air Force AC-130 gunships would arrive overhead to protect the rescue force from any Iranian counterattack and to

destroy the jet fighters at the Tehran airport.

The choppers would fly the rescue force and the freed hostages

to an abandoned air base at Manzariyeh, about 50 miles southwest of Tehran, which was to be seized and protected by a Ranger

company flown in on C-130s.

The helicopters would be destroyed and C-141s, flown in from Saudi Arabia, would

then fly the entire group to a base in Egypt.

USAF Col. James Kyle, mission planner and on-scene commander, and Army Col. Charles Beckwith, Delta Force commander, flew

to Desert One in an MC-130, like this one, with Delta troopers and an Air Force combat controller team.(Air Force Association

photo)

Here is a link to the original location of this article from the Air Force Association:

Desert One

The mission was to rescue the hostages held in Iran, but it ended in disaster.

Iranian soldiers

survey the wreckage of the aborted US military attempt to rescue hostages in the US Embassy in Tehran. Eight American servicemen

died in a disastrous accident as the rescue forces pulled back from the mission.

By Otto Kreisher

For some,

the current political debate over the combat readiness of today's American military stirs memories of a long-ago event that,

more than anything else, came to symbolize the disastrously "hollow" forces of the post-Vietnam era.

It

began in the evening of April 24, 1980, when a supposedly elite US military force launched a bold but doomed attempt to rescue

their fellow American citizens and their nation's honor from captivity in Tehran. In the early hours of April 25, the effort

ended in fiery disaster at a remote spot in Iran known ever after as Desert One.

This failed attempt to rescue 53

hostages from the US Embassy in Tehran resulted in the death of five US Air Force men and three Marines, serious injuries

to five other troops, and the loss of eight aircraft. That failure would haunt the US military for years and would torment

some of the key participants for the rest of their lives.

One, Air Force Col. James Kyle, called it, "The most

colossal episode of hope, despair, and tragedy I had experienced in nearly three decades of military service."

The

countdown to this tragedy opened exactly 20 years ago, in January 1979. A popular uprising in Iran forced the

sudden abdication

and flight into exile of Shah Mohammed Reza Pahlavi, the longtime ruler of Iran and staunch

US ally. Brought to power

in the wake of this event was a government led, in name, by Shahpur Bakhtiar and

Abolhassan Bani Sadr. Within months,

they, too, had been shoved aside, replaced by fundamentalist Shiite Muslim

clerics led by Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini.

This secretly taken photo shows how Iranian troops blanketed the streets, making it difficult for the US to

obtain intelligence. The CIA's spy network had been dismantled, one of many problems facing the rescue planners.

On Nov. 4, two weeks after President Jimmy Carter had allowed the shah to enter the US for medical care, 3,000 Iranian

"student" radicals invaded the US Embassy in Tehran, taking 66 Americans hostage. Chief of Mission L. Bruce Laingen

and two aides were held separately at the Iranian Foreign Ministry.

The students demanded that the shah be returned

for trial. Khomeini's supporters blocked all efforts to free the hostages.

Thirteen black and female hostages would

be released later as a "humanitarian" gesture, but the humiliating captivity for the others would drag on for 14

months.

Rice Bowl

Carter, facing a re-election battle in 1980, strongly favored a diplomatic solution, but

his national security advisor, Zbignew Brzezinski, directed the Pentagon to begin planning for a rescue mission or retaliatory

strikes in case the hostages were harmed. In response, the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, Air Force Gen. David C.

Jones, established a small, secretive planning group, dubbed "Rice Bowl," to study American options for a rescue

effort.

It quickly became clear how difficult that would be.

The first obstacle was the location. Tehran

was isolated, surrounded by more than 700 miles of desert and mountains in any direction. This cut the city off from ready

attack by US air or naval forces. Moreover, the embassy was in the heart of the city congested by more than four million people.

A bigger hurdle, however, was the condition of the US military, which had plummeted in size and quality in the seven

years since it had staged a near-total withdrawal from Vietnam. Among the casualties of the postVietnam cutbacks was the

once-powerful array of Army and Air Force special operations forces that had performed feats of great bravery and military

skill in Southeast Asia.

The one exception was an elite unit of soldiers recently formed to counter the danger of

international terror. This unit, called Delta Force, was commanded by Army Col. Charles Beckwith, a combat-tested special

forces officer. Delta, which had just been certified as operational after conducting a hostage rescue exercise, was directed

to start planning for the real thing at the Tehran embassy.

The immediate question was how to get Delta close enough

to do its job. Directing the planners who were trying to solve that riddle was Army Maj. Gen. James Vaught, a veteran of three

wars, with Ranger and airborne experience but no exposure to special operations or multiservice missions. Because of the need

for extreme secrecy, he was denied the use of an existing JCS or service organization. Vaught had to assemble his planning

team and the joint task force that would conduct the mission from widely scattered sources.

One of the early selections

was Kyle, a highly regarded veteran of air commando operations in Vietnam, who would help plan the air mission and would be

on-scene commander at Desert One.

When Beckwith ruled out a parachute drop, helicopters became the best option for

reaching Tehran, despite the doubts Beckwith and other Vietnam veterans had about their reliability. Navy RH-53D Sea Stallions,

which were used as airborne minesweepers, were chosen because of their superior range and load-carrying capability and their

ability to operate from an aircraft carrier.

Even the Navy Sea Stallions could not fly from the Indian Ocean to Tehran

without refueling. After testing and rejecting alternatives, the task force opted to use Air Force EC-130 Hercules transports

rigged with temporary 18,000-gallon fuel bladders to refuel the helicopters on their way to Tehran.

Finding the Spot

However, that decision led to the requirement of finding a spot in the Iranian desert where the refueling could take

place on the ground. That required terrain that would support the weight of the gas-bloated Hercules.

US intelligence

found and explored just such a location, about 200 miles southeast of Tehran. In planning and training, this site was known

as Desert One.

Because the RH-53s were Navy aircraft, the Pentagon assigned Navy pilots to fly them and added Marine

copilots to provide experience with land assault missions.

That combination soon proved unworkable, as many of the

Navy's pilots were unable or unwilling to master the unfamiliar and difficult tasks of long-range, low-level flying over land,

at night, using primitive night vision goggles.

In December, most of the Navy pilots were replaced by Marines carefully

selected for their experience in night and low-level flying. The mission ultimately had 16 pilots: 12 Marine, three Navy,

and one Air Force.

Selected to lead the helicopter element was Marine Lt. Col. Edward Seiffert, a veteran H-53 pilot

who had flown long-range search-and-rescue missions in Vietnam and had considerable experience flying with night vision goggles.

Beckwith described Seiffert as "a no-nonsense, humorless--some felt rigid--officer who wanted to get on with

the job."

Delta and the helicopter crews never developed the coordination and trust that are essential to high-stress,

complex combat missions. Possibly, this was caused by the disjointed nature of the task force and its training.

While

the helicopter crews worked out of Yuma, Ariz., the members of Delta Force did most of their training in the woods of North

Carolina. Other Army personnel were drilling in Europe. The Air Force crews that would take part in the mission trained in

Florida or Guam, thousands of miles away in the Pacific.

The entire operation was being directed by a loosely assembled

staff in Washington, D.C., which insisted that all the elements had to be further isolated by a tightly controlled flow of

information that would protect operational

security.

"Ours was a tenuous amalgamation of forces held together

by an intense common desire to succeed, but we were slow coming together as a team," Kyle wrote in his account of the

mission.

Meanwhile, Beckwith and his staff were desperate for detailed information on the physical layout of the

embassy, the numbers and locations of the Iranian guards, and, most important, the location of the hostages.

C-130s

were to fly the rescue force from Masirah to Desert One. Helicopters, flown from Nimitz, would carry the rescuers to a hideout

near Tehran. The next night, the commandos were to drive to the embassy to release the hostages. The helicopters then were

to carry the rescuers and hostages to the abandoned Manzariyeh air base, where C-141s would fly them to Egypt.

Six

Buildings

Without that data, Delta had to plan to search up to six buildings in the embassy compound where the hostages

might be held. That required Beckwith to increase the size of his assault force, which meant more helicopters were needed.

No intelligence was coming out of Iran because Carter had dismantled the CIA's network of spies due to the agency's

role in overthrowing governments in Vietnam and Latin America.

It would be months before agents could be inserted

into Iran to supply the detailed intelligence Beckwith said was "the difference between failure and success, between

humiliation and pride, between losing lives and saving them."

Despite all the obstacles, the task force by mid-March

1980 had developed what they considered a workable plan, and all of the diverse operational elements had become confident

of their ability to carry it out.

The plan was staggering in its scope and complexity, bringing together scores

of aircraft and thousands of men from all four services and from units scattered from Arizona to Okinawa, Japan.

The plan was this:

On the first night, six Air Force C-130s carrying 132 Delta commandos, Army Rangers, and support

personnel and the helicopter fuel would fly from the island of Masirah, off the coast of Oman, more than 1,000 miles to Desert

One, being refueled in flight from Air Force KC-135 tankers.

Eight Navy RH-53Ds would lift off the aircraft carrier

USS Nimitz, about 50 miles south of the Iranian coast, and fly more than 600 miles to Desert One.

After refueling,

the helicopters would carry the rescue force to a hideout in hills about 50 miles southeast of Tehran, then fly to a separate

hiding spot nearby. The C-130s would return to Masirah, being refueled in flight again.

The next night, Delta would

be driven to the embassy in vehicles obtained by the agents. A team of Rangers would go to rescue the three Americans held

in the foreign ministry.

As the ground units were freeing the hostages, the helicopters would fly from their hiding

spot to the embassy and the foreign ministry.

Three Air Force AC-130 gunships would arrive overhead to protect the

rescue force from any Iranian counterattack and to destroy the jet fighters at the Tehran airport. The choppers would fly

the rescue force and the freed hostages to an abandoned air base at Manzariyeh, about 50 miles southwest of Tehran, which

was to be seized and protected by a Ranger company flown in on C-130s.

The helicopters would be destroyed and C-141s,

flown in from Saudi Arabia, would then fly the entire group to a base in Egypt.

"Now a Reality"

After

five months of planning, organizing, training, and a series of increasingly complex rehearsals, Kyle recalled: "The ability

to rescue our people being held hostage, which didn't exist on Nov. 4, 1979, was now a reality." The team still needed

Carter's permission to execute.

Although the shah had moved to Panama and then to Egypt, the 53 Americans remained

hostages and the public was getting impatient. Finally, in a White House meeting of his top advisors on April 11, Carter gave

up on diplomacy. "I told everyone that it was time for us to bring our hostages home; their safety and our national honor

were at stake," Carter said in his memoirs.

Five days later, Jones, Vaught, and Beckwith briefed Carter at the

White House on the plans for the rescue mission and expressed their confidence in their ability to pull it off.

Beckwith

recalled that Carter told them: "I do not want to undertake this operation, but we have no other recourse. ... We're

going to do this operation."

Carter then told Jones, "This is a military operation; you will run it. ...

I don't want anyone else in this room involved."

The audacious operation was code-named "Eagle Claw."

The target date was April 24-25.

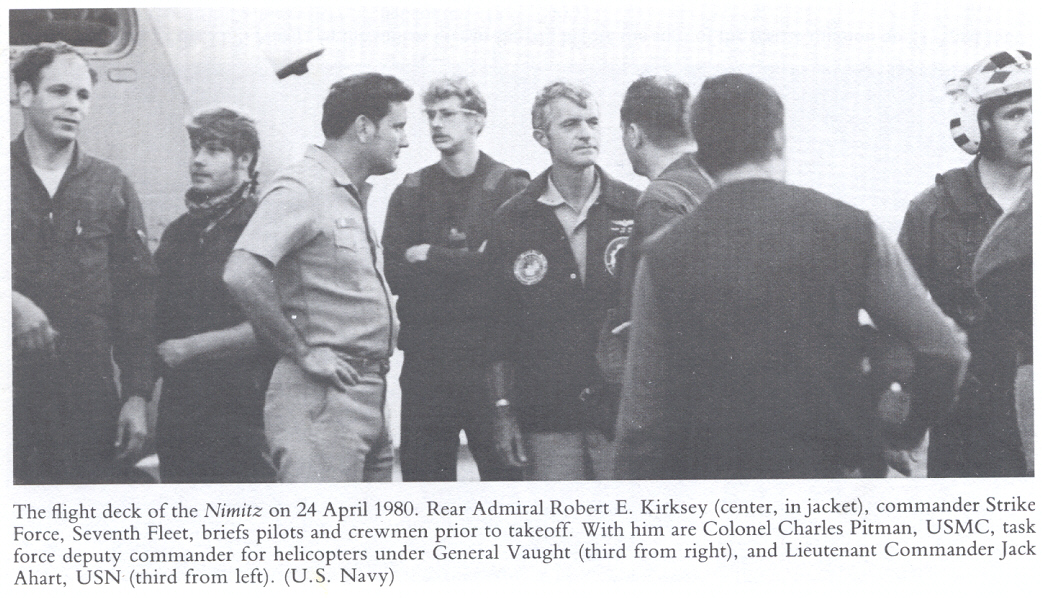

Almost immediately, forces began to move to their jump-off points. By April 24,

44 aircraft were poised at six widely separated locations to perform or support the rescue mission. The RH-53s already were

on Nimitz, where they had been stored with minimal care for months, but a frantic effort brought them up to what Seiffert

and Navy officials insisted was top mechanical condition by launch day.

Beckwith and Seiffert had agreed that they

would need a minimum of six flyable helicopters at Desert One for the mission to continue. Beckwith had asked for 10 helos

on the carrier to cover for possible malfunctions, but the Navy claimed they could not store more than eight on the hangar

deck.

Delta and many of the Air Force aircraft staged briefly at a Russian-built airfield at Wadi Qena, Egypt, which

would serve as Vaught's headquarters for the mission. While at Wadi Qena on April 23, the task force received an intelligence

report that all 53 hostages were being held in the embassy's chancery. Because he was not told the solid source of that information,

Beckwith did not trust it enough to reduce his assault force, which may have been a critical decision.

The next day,

with Delta Force and support elements on Masirah and the helicopter crews on Nimitz, Vaught received the final weather report.

It promised the virtually clear weather that the mission required.

"Execute Mission"

Vaught sent a

message to all units: "Execute mission as planned. God speed."

"There was cheering, and fists were

jammed into the air with thumbs up. ... This was an emotional high for all of us," Kyle wrote.

That emotional

high would crash into despair in about 12 hours.

The mission started in the twilight of April 24 with barely a hitch.

Kyle and Beckwith flew out of Masirah on the lead MC-130 Combat Talon with some of the Delta troopers and an Air Force combat

controller team. At about the same time, Seiffert led the helicopter force--given the call sign of "Bluebird"--from

Nimitz and headed to the Iranian coast, 60 miles away.

The choppers had been fitted with two advanced navigation

systems, but the pilots found them unreliable and were relying mainly on visual navigation as they cruised along at 200 feet.

"We were fat, dumb, and happy," Seiffert recalled.

About 100 miles into Iran, the Talon ran into a thin cloud

that reduced visibility but was not a problem at its cruise altitude of 2,000 feet. The cloud was a mass of suspended dust,

called a "haboob," common to the Iranian desert. Air Force weather experts supporting the mission knew it was a

possibility but apparently never told the mission pilots. Kyle said he considered sending a warning to the helicopters but

decided it was not significant.

When the MC-130 ran into a much thicker cloud later, he did try to alert Seiffert,

but the message never got through. It was just one of the communications glitches that would plague the mission.

The

dust cloud that was a minor irritation to the Combat Talon became an extended torture for the helicopter pilots, who were

trying to fly formation and visually navigate at 200 feet while wearing the crude night vision goggles. Visibly shaken Marine

fliers later told Beckwith and Kyle the hours in the milk-like dust cloud were the worst experience of their lives, which

for some included combat in Vietnam.

Things had started to go wrong even before the dust cloud.

Less than

two hours into the flight, a warning light came on in the cockpit of Bluebird Six. The indicator, called the Blade Inspection

Method, or BIM, warned of a possible leak of the pressurized nitrogen that filled the Sea Stallion's hollow rotors. In the

H-53 models the Marines were used to flying, the BIM indicator usually meant a crack in one of the massive blades, which had

caused rotor failures and several fatal crashes in the past. As a result, Marine H-53 pilots were trained to land quickly

after a BIM warning.

The Navy's RH-53s, however, had newer BIM systems that usually did not foretell a blade failure.

To that date, no RH-53 had experienced a blade break and the manufacturer had determined that the helicopter could fly safely

for up to 79 hours at reduced speed after a BIM alert.

Down to Seven

However, the pilots of Bluebird Six

did not know that. Thinking the craft unsafe to fly, the crew abandoned it in the desert and jumped aboard a helicopter that

had landed to help.

The mission was down to seven helicopters.

Further inland, the remaining choppers were

struggling with the dust cloud, which dropped visibility to yards and sent the cockpit temperature soaring. Although all the

pilots were having difficulty, Bluebird Five was really suffering as progressive electrical system failures took away most

of the pilot's essential flight and navigation instruments. The pilot, Navy Lt. Cmdr. Rodney Davis, "was flying partial

panel, needle-ball, wet compass--a real vertigo inducer," Seiffert said.

Fighting against the unnerving effects

of vertigo-when your inner ear tells you the aircraft is turning while your eyes tell you it is not-and unaware of the location

of the other helicopters or the weather at Desert One, Davis decided to turn back.

Davis did not know that he was

about 25 minutes from clear air, which prevailed all the way to Desert One, because everyone was maintaining strict radio

silence to avoid detection.

The mission now was down to the minimum six helicopters.

Meanwhile, the lead

C-130 had landed at Desert One, and Beckwith's commandos had raced out to block the dirt road that traversed the site.

Within minutes, they stopped a bus with 44 persons at one end of the site and at the opposite end had to fire an anti-tank

round into a gas tanker truck that refused to stop. The driver of the tanker leaped from his burning vehicle and escaped in

a pickup that was following. Despite fears the mission might be compromised, the combat controllers quickly installed a portable

navigation system and runway lights to guide the other mission aircraft to Desert One.

Soon, the remainder of Delta

Force was on the ground and the three EC-130s were positioned to refuel the helicopters, which were supposed to arrive 20

minutes later.

But, as Kyle discovered months later, someone had miscalculated the choppers' flight time by 55 minutes

and the first Bluebird was more than an hour away. Finally, the Sea Stallions lumbered in from the dark, coming in ones and

twos, instead of a formation, and from different directions.

After considerable anxiety, the count was up to six

helicopters on the ground at Desert One and the hopes for a successful rescue soared again.

But as the helicopters

struggled through unexpected deep sand to get into position behind the tankers, one shut down its engines.

Bluebird Two

had suffered a complete failure of its secondary hydraulic system, which was unrepairable and left it with minimal pressure

for its flight controls. Although the pilot appeared willing to try taking his sick bird on to the hideout, Seiffert overruled

him.

Kyle tried to talk Seiffert into taking the helo on, but he refused, warning that flying with the one system

at such heavy weight and high temperature could result in a control lockup and a crash that would kill not only the crew but

the Delta commandos on board. Kyle then asked Beckwith if he could reduce his assault force to go with five choppers, but

he was equally adamant about not changing his plans.

Failure of Eagle Claw

It seemed clear the mission had

to be aborted.

Kyle informed Vaught of the situation by satellite radio and the task force commander relayed that

to Jones and the Secretary of Defense, Harold Brown, at the Pentagon. When the word got to the White House, Carter asked Brown

to get Beckwith's opinion. Told that Beckwith felt it necessary to abort, Carter said: "Let's go with his recommendation."

Eagle Claw had failed and the tense anticipation of success drained into frustration and anger.

Now Kyle

was left with the unrehearsed job of getting everyone out of Iran. Because of the extended time on the ground, one of the

C-130s was running low on fuel and had to leave soon. To allow that tanker to move, Kyle directed Marine Maj. James Schaefer

to reposition his helicopter. With a flattened nose wheel, Schaefer could not taxi and tried to lift off to move his bird,

stirring a blinding dust cloud.

As Kyle watched in horror, the helo slid sideways, slicing into the C-130 with its

spinning rotors and igniting a raging fire. Red-hot chunks of metal flamed across the sky as munitions in both aircraft torched

off.

Some of the Delta commandos had boarded the C-130 and they came tumbling out the side door as the Air Force

loadmasters and senior soldiers tried to stop a spreading panic. Men were helping the injured away from the inferno.

The projectiles ejecting from the flaming wreckage were hitting the three nearby helicopters and their crews quickly fled.

Many of the people at Desert One that night credit Kyle with restoring order to the chaotic scene and getting all

the living men and salvageable equipment out safely. But in the flaming funeral pyre of Eagle Claw's shattered hopes, they

left the bodies of eight brave men.

On the departing C-130s, Delta medics treated four badly burned men, including

Schaefer, his copilot, and two airmen. "We left a lot of hopes and dreams back there at Desert One, but the nightmares

and despair were coming with us ... and would continue to haunt us for years, maybe forever," Kyle wrote later.

The hostages were released in January 1981 after the US and Iran reached an accord involving release of frozen

Iranian assets. Lt. Col David Roeder, left, and Col. Thomas E. Schaefer were two of the USAF servicemen who were among

those freed.

Holloway's Investigation

Although Carter went on television the next day to announce the

failure of the mission and to accept the blame, Congress and the Pentagon launched inquiries to determine the reasons for

the tragedy. The Pentagon probe was handled by a board of three retired and three serving flag officers representing all four

services; it was led by retired Adm. James L. Holloway III. The commission's report listed 23 areas "that troubled us

professionally about the mission-areas in which there appeared to be weaknesses."

"We are apprehensive

that the critical tone of our discussion could be misinterpreted as an indictment of the able and brave men who planned and

executed this operation. We encountered not a shred of evidence of culpable neglect or incompetence," the report said.

The commission concluded that the concept and plan for the mission were feasible and had a reasonable chance for

success.

But, it noted, "the rescue mission was a high-risk operation. ... People and equipment were called

upon to perform at the upper limits of human capacity and equipment capability. There was little margin to compensate for

mistakes or plain bad luck."

The major criticism was of the "ad hoc" nature of the task force, a chain

of command the commission felt was unclear, and an emphasis on operational secrecy it found excessive.

The commission

also said the chances for success would have been improved if more backup helicopters had been provided, if a rehearsal of

all mission components had been held, and if the helicopter pilots had had better access to weather information and the data

on the RH-53s' BIM warning system.

And it suggested that Air Force helicopter pilots might have been better qualified

for the mission.

However, the report also said, "The helicopter crews demonstrated a strong dedication toward

mission accomplishment by their reluctance to abort under unusually difficult conditions." And it concluded that, "two

factors combined to directly cause the mission abort: an unexpected helicopter failure rate and the low-visibility flight

conditions en route to Desert One."

Beckwith openly blamed the helicopter pilots immediately after the mission.

However, in his critique to the Senate Armed Services Committee, he attributed the failure to Murphy's Law and the use of

an ad hoc organization for such a difficult mission. "We went out and found bits and pieces, people and equipment, brought

them together occasionally, and then asked them to perform a highly complex mission," he said. "The parts all performed,

but they didn't necessarily perform as a team."

He recommended creating an organization that, in essence, was

the prototype of the Special Operations Command that Congress mandated in 1986.

Kyle, in his book on the mission,

rejected the Holloway commission's conclusions and basically blamed Seiffert and the helicopter pilots for not climbing out

of the dust cloud, for not using their radios to keep the formation intact, and for the three helicopter aborts.

He

argued that the task force never had less than seven flyable helicopters. All that was lacking, he wrote, was "the guts

to try."

Seiffert praised Beckwith and Kyle as professional warriors but disagreed with their criticism of him

and his helicopter pilots. He equated his decision to ground the chopper with the failed hydraulic system to Beckwith's refusal

to cut his assault force, and he refused to second-guess the two pilots who had aborted earlier.

Seiffert said he

was confident that, had they gotten to Tehran, the mission would have succeeded. Kyle was equally certain, writing that: "It

is my considered opinion that we came within a gnat's eyebrow of success."

Beckwith wrote in his memoirs that

he had recurring nightmares after Desert One. However, he noted, "In none have I ever dreamed whether the mission would

have been successful or not."

Otto Kreisher is the national security reporter for Copley News Service,

based in Washington, D.C. His most recent article for Air Force Magazine, "To Protect the Force," appeared in the

November 1998 issue.

This is an Air Force AC-130, a flying cannon. It has high speed machine guns and automatic cannons, and can fill a football

field with a bullet in every square inch in a matter of seconds. These were the Air Force's protection they provided. They

would also have been used to keep any Iranian aircraft from taking off from any airfield in the area, and also to keep the

streets clear of any Iranians from around the embassy.

The RH-53 was a fine aircraft. Why everything went wrong is what we will ask ourselves for ever. It just seems that God did

not want us to win that day, we did not have his favor.

This story below is copied from the Air Force magazine, THE AIRMAN. Click on this link to go to the original story. All credit

for this story goes to THE AIRMAN.

|

A mission of hope turned tragic. A case of what could've been.

by Master Sgt. Jim Greeley |

|

| Nov. 4, 1979 — More than

3,000 Iranian militant students storm the U.S. Embassy in Tehran, Iran, taking 66 Americans hostage and setting the stage

for a showdown with the United States.

April 25, 1980 — A defining moment for President Jimmy

Carter, for the American people and for America’s military. At 7 a.m. a somber President Carter announces to the nation,

and the world, that eight American servicemen are dead and several others are seriously injured, after a super-secret hostage

rescue mission failed.

April 26, 1980 — Staff Sgt. J.J. Beyers lies unconscious

in a Texas hospital bed. The Air Force radio operator was one of the lucky few C-130 aircrew members to survive a ghastly

collision and explosion between his aircraft and a helicopter on Iran’s Great Salt Desert. The accident took place after

the rescue team was forced to abort its mission at a location from then on known as Desert One.

|

| The living room walls in J.J.

Beyers’ Florida home tell a story of intense pride and patriotism — a shrine to days and friends long past. The

dark paneling in this modest, single-story house is the canvas for a riveting collection of photos, citations and plaques.

Although faded over the years, the collection possesses an unspoken power. |

| Former Staff Sgt. J.J. Beyers |

|

|

| nearly burned to death during the rescue attempt |

Former Staff Sgt. J.J. Beyers nearly burned to death during the

rescue attempt. Knocked out after the initial explosion, he awoke to find himself on fire. He crawled halfway to an open door

at the back of the aircraft when two Army troopers, hearing his screams, came back into the burning aircraft and pulled him

to safety. Despite that, he believes the mission would’ve succeeded if the Army team had made it to the U.S. Embassy.

Beyers’ hands and arms tell another side of the story. Settling

into his favorite recliner, the former Air Force sergeant rolls up the sleeves of his checkered shirt. The scars on his arms

and his disfigured hands tell their own harrowing tale. Even after all these years, the tale of courage, hope, pain, fear

and disappointment jump out and scream, listen!

In 1980, Beyers was part of an elite group of airmen, soldiers,

sailors and Marines who volunteered for Operation Eagle Claw — a bold and daring rescue attempt of Americans held hostage

in Tehran, Iran.

| RH-53 Sea Stallion helicopters lined up |

|

|

| on the flight deck of the nuclear-powered aircraft carrier USS Nimitz |

DOD Archive Photo

Crews make final checks on three of the eight RH-53 Sea Stallion

helicopters lined up on the flight deck of the nuclear-powered aircraft carrier USS Nimitz in preparation for Operation Evening

Light, the Navy code name for the rescue mission to Iran. For the mission to go forward, six of the eight RH-53s had to make

it into Iran in working order. Six of them did. But just before heading out to their next staging point, one developed a hydraulic

problem, and the mission was scrubbed.

Beyers’ scars and mementos are emblematic of the rescue mission.

They’re constant reminders of the friends he lost. A reminder of the disaster he survived. A reminder of what could’ve

been.

“I was lucky,” Beyers said. “I lived.”

Five of his crewmates from the 8th Special Operations Squadron

at Hurlburt Field, Fla., died in the Iranian desert, along with three Marine helicopter crewmen (See “Remembering Heroes,”

Page 9).

| The burned out wreckage of one of the RH-53 |

|

|

| An intact RH-53 sits in the background |

courtesy 16th SOW Historian

The burned out wreckage of one of the RH-53 Sea Stallion helicopters

was discovered and photographed the next morning by the Iranian military. An intact RH-53 sits in the background. It was decided

during the evacuation from Desert One not to destroy the remaining helicopters for fear of damaging the C-130s, the force’s

ride out of Iran. “The accident was a calamity heaped on despair. It was devastating,” wrote retired Col. James

Kyle in his book, “The Guts to Try.” He was the on-scene commander at Desert One.

|

“They were a brave, courageous and determined group of guys,”

Beyers said. “I miss them.”

Countdown to tragedy

The countdown to Desert One began in spring

1979 when a popular uprising in Iran forced longtime Iranian ruler, Shah Mohammed Reza Pahlavi, into exile. After months of

internal turmoil, the Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeni, a Shiite Muslim cleric, took power in the country.

On Nov. 4, 1979, just a few weeks after President Jimmy Carter

allowed the Shah to enter the United States for medical treatment, thousands of Iranian students stormed the American Embassy

in Tehran, taking 66 hostages and demanding the return of the Shah to stand trial in Iran.

American diplomatic efforts to release the hostages were thwarted

by Khomeni supporters. At the same time, Pentagon planners began examining rescue options.

Planning

a rescue

The original intent was to launch a rapid rescue effort. But, every quick-reaction alternative was dismissed.

For planners, the situation was bleak. Intelligence information was difficult to get. The hostages were heavily guarded in

the massive embassy compound. Logistically, Tehran was a city crammed with 4 million people, yet it was very isolated —

surrounded by about 700 miles of desert and mountains in every direction. There was no easy way to get a rescue team into

the embassy.

One scenario was parachuting an elite Army special forces team

in. The team would fight its way in and out of the embassy, rescuing the hostages along the way. That plan was deemed suicidal. |

|

| After realizing there was no infrastructure or support

for a quick strike, planners started mapping out a long-range, multifaceted rescue.

What emerged was a complex, two-night operation. An Army rescue

team would be brought into Iran with a combination of helicopters and C-130s. The “Hercs” would fly the troopers

into a desert staging area from Oman. They would load the rescue team on the helicopters, refuel the choppers, and then the

helos and shooters would move forward to hide in areas about 50 miles outside Tehran.

On day two, the Army team would be escorted to the embassy in trucks

by American intelligence agents. The Army team would take down the embassy, rescue the hostages and move them to a nearby

soccer stadium. The helos would pick up the shooters and hostages at the stadium and evacuate them to Manzariyeh Air Base,

about 40 miles southeast of Tehran.

MC-130s would fly Army Rangers and combat controllers into Manzariyeh.

The Rangers would take the field and hold it for the evacuation. Meanwhile, AC-130H Spectre gunships would be over the embassy

and the airfield to “fix” any problems encountered. Finally, C-141s would arrive at Manzariyeh to fly the hostages

and rescue team to safety.

Secrecy and surprise were critical to the plan. The entire mission

would be done at night, and surprise was the Army shooters’ greatest advantage.

It was an ambitious plan; some say too ambitious.

“This mission required a lot of things we had never done

before,” said retired Col. (then-Capt.) Bob Brenci, the lead C-130 pilot on the mission. “We were literally making

it up as we went along.”

Flying using night-vision goggles was almost unheard of. There

was no capability, or for that matter, a need, to refuel helicopters at remote, inaccessible landing zones. All these skills

and procedures would be tested and honed for this mission.

“These capabilities are routine now for special operators,

but at the time we were right there on the edge of the envelope,” said retired Col. (then-Capt.) George Ferkes, Brenci’s

co-pilot.

The aircrews weren’t the only ones pushing the envelope.

Airman First Class Jessie Rowe was a fuels specialist at MacDill Air Force Base, Fla., when he got a late night call to pack

his bags and show up at the Tampa International Airport. He met his boss, Tech. Sgt. Bill Jerome, and the pair flew to Arizona.

They were now a part of Eagle Claw. Their job? Devise a self contained refueling system the C-130s could carry into the desert

to refuel the helicopters at the forward staging area.

“No one told us why,” said Rowe, who’s now a

major at Hurlburt Field and one of just two operation participants still on active duty. “But, you didn’t need

to be a rocket scientist to figure it out.

“We begged, borrowed and stole the stuff we needed to make

it work,” he said. “We got it done. In less than a month, we had a working system.”

The Eagle Claw players were spread out, training around the world.

The Hurlburt crews spent most of their time training in Florida and the southwestern United States. The pieces were coming

together.

At the same time, negotiations to free the hostages continued to

go nowhere. By the time April 1980 rolled around, the Eagle Claw team had been practicing individually, and together, for

five months. The aircrews averaged about 1,000 flying hours in that time. In comparison, a typical C-130 crew dog would take

three years to log 1,000 hours.

It’s showtime

“We were chomping at the bit,” Brenci said.

“We just wanted to go and do it.”

After a long training mission in Arizona and a flight to Nellis

Air Force Base, Nev., to pick up parts, Col. J.V.O. Weaver (a captain then) and his crew, returned to Hurlburt Field to an

unusual sight.

“We rolled in and noticed the maintenance guys were on the

line painting all the birds flat black,” Weaver said. “They painted everything. Tail numbers, markings. Everything.”

The plan was moving forward. Less than a day later, six C-130s

quietly departed Florida bound for Wadi Kena, Egypt. The president hadn’t pulled the trigger yet, but the hammer was

cocked on the operation.

The Army and Air Force troops were in Egypt awaiting orders. The

Marines and sailors, the helicopter contingent, were aboard the USS Nimitz afloat in the Persian Gulf off the coast of Iran.

“I remember we ate C-rats (the predecessor to MREs) for days

and then one morning a truck rolls up, and we’re served a hot breakfast,” Rowe said. “Light bulbs went on

in everyone’s minds.”

The hot breakfast was a precursor to a briefing and pep talk from

Army Maj. Gen. James Vaught, the Joint Task Force commander for Eagle Claw. The mission was a go.

“Everyone was pumped up,” said retired Chief Master

Sgt. Taco Sanchez (then a staff sergeant). “Arms were in the air. We were ready!”

Next stop, Masirah. A tiny island off the coast of Oman. To say

this air patch was desolate would be kind. It was a couple of tents and a blacktop strip. It was the final staging area —

the last stop before launching.

Just before sunset on April 24, Brenci’s MC-130 took off

toward Desert One. The die was cast. Brenci’s crew would be the first to touch down in Iran. They carried the Air Force

combat control team and Army Col. Charlie Beckwith’s commandos. Beckwith would lead the rescue mission into the embassy.

Also on board Brenci’s plane was Col. James Kyle, the on-scene commander at Desert One and one of the lead planners

for the operation. The other Hercs left Masirah after dark, and the helicopters launched off the Nimitz.

It was a four-hour flight. Plenty of time to contemplate what they

were attempting.

“We just tried to stay busy,” Sanchez said. “We

were in enemy territory now. The pucker factor was pretty high.”

The first challenge would be to find the make-shift landing strip.

Only 21 days earlier, Maj. John Carney, a combat controller, had flown a covert mission into Iran with the CIA to set up an

infrared landing zone at Desert One. Carney was perched over Brenci’s shoulder as the C-130 neared the landing site.

The lights he had buried in the desert would be turned on via remote control from the C-130’s flight deck. The question

was, would they work?

Brenci was a couple miles out when in slow succession a “diamond-and-one”

pattern appeared through his night-vision goggles. The bird touched down in the powdery silt, and the troops went to work.

Gremlins

arrive

The choppers, eight total, left the Nimitz and were supposed to fly formation, low level, to the meet area.

Because of the demands of the mission, at least six helicopters were needed at Desert One for the mission to go forward. Two

hours into the flight the first helicopter aborted.

Further inland, the Marine helo pilots met their own private hell.

Weather for the mission was supposed to be clear. It wasn’t. Flying at 500 feet, the helicopters got caught in what

is known in the Dasht-e-Kavir, Iran’s Great Salt Desert, as a “haboob” — a blinding dust storm. The

situation was bad. After battling the storm for what seemed like days, one of the helicopters turned back.

At Desert One, all the C-130s had landed and were taxied into place.

They were waiting for the choppers. An hour late, the first helicopter arrived.

“We weren’t on the ground that long, but my God, it

felt like an eternity waiting for the helos,” Beyers recalled. The first two helicopters to roll in pulled up to Beyer’s

aircraft to be refueled. When the sixth chopper showed, everyone breathed a sigh of relief.

The Army troops boarded the helicopters. The fuels guys did their

magic. Everything was good. Then word spread. One of the helicopters had a hydraulic failure. Game over.

Beckwith needed six helicopters. Kyle, the on-scene commander,

aborted the mission.

“It was crushing,” Rowe said. “We had come all

that way, spent all that time practicing, and now we had to turn back.”

The decision made, now the crews had to evacuate the Iranian dust

patch. Time was a factor. The C-130s were running low on fuel. Sunrise was fast approaching, and the team didn’t want

to be caught on the ground by Iranian troops. Members had already detained a civilian bus with 40-plus passengers and were

forced to blow up a fuel truck, which wouldn’t stop for a roadblock.

They had worn out their welcome. Dejected and disappointed, they

just wanted to button up and go home.

Beyers’ aircraft, flown by Capt. Hal Lewis, was critically

low on fuel. But, before it could depart, the helicopter behind the aircraft had to be moved.

“We had just taken the head count,” recalled Beyers.

They had 44 Army troops on board. Beyers was on the flight deck behind Lewis’ seat. “We got permission to taxi

and then everything just lit up.”

A fireball engulfed the C-130. According to witnesses, the helicopter

lifted off, kicked up a blinding dust cloud, and then banked toward the Herc. Its rotor blades sliced through the Herc’s

main stabilizer. The chopper rolled over the top of the aircraft, gushing fuel and fire as it tumbled.

Burning wreck

Fire

engulfed the plane. Training kicked in. The flight deck crew began shut-down procedures. The fire was outside the plane. Beyers

headed down the steps toward the crew door. That’s when someone opened the escape hatch on top of the aircraft in the

cockpit, Beyers said. Boom. Black out.

Tech. Sgt. Ken Bancroft, one of three loadmasters on the airplane,

knew he had troops to get off the plane. He went to the left troop door. Fire. Right troop door. Jammed shut.

“I don’t know how I got that door off,” Bancroft

said. |

by Master Sgt. Dave Nolan

Retired Tech. Sgt. Ken Bancroft is a hero, according to some operation

participants. With fire on one side of the aircraft, the main crew entry door engulfed in flames, and the left parachute door

jammed, he somehow broke the door free and began throwing some 40 Army commandos out of the burning aircraft. “I was

just doing my job,” he said. “I’m no hero.”

He did. One after another, this hulk of a man tossed the Army troops

off the burning plane like a crazed baggage handler unloading a jumbo jet.

Beyers had been knocked out. The flight deck door had hit him on

the head as he went down the steps. When he came to, he was on fire. Conscious again, he crawled toward the rear of the plane.

“I made it halfway,” Beyers said. “I quit. I

knew I was dead.” Somehow he moved himself closer to the door. Then he saw two figures appear through the flames. Two

Army troopers had come back for him. He was alive, but in bad shape.

Beyers always had the bad habit of rolling up his flight suit sleeves.

He finally paid the price. His arms, from the elbows down, were terribly burned. His hands were charred. Hair, eyebrows and

eyelashes, gone. Worse were the internal injuries. His lungs, mouth and throat were burned. Yet, he clung to life.

The desert scene was one of organized chaos. Failure had turned

to tragedy.

“I knew they were dead,” Bancroft said of his crew

mates in the front of the plane. “I looked up there, and it was just a wall of fire. There was nothing I could do.”

The last plane left Desert One a half hour after the accident.

Beyers was on that airplane.

“The accident was a calamity heaped on despair. It was devastating,”

wrote Kyle in his book called “The Guts to Try.”

“The C-130 crews and combat controllers had not failed in

any part of the operation and had a right to be proud of what they accomplished,” Kyle said. “They inserted the

rescue team into Iran on schedule, set up the refueling zone, and gassed up the helicopters when they finally arrived. Then,

when things went sour, they saved the day with an emergency evacuation by some incredibly skillful flying. They had gotten

the forces out of Iran to fight another day — a fact they can always look back on with pride.”

Pride and sorrow are the two mixed emotions most participants share.

“We were the ultimate embarrassment,” Sanchez said.

“Militarily we did some astounding things, but ultimately we failed America. I’m proud of what we accomplished.

I was 27 years old, and when I think about that mission it still sends shivers down my spine.”

The aftermath of the rescue operation was a barrage of investigations,

congressional hearings and, believe it or not, more planning and training for a follow-on rescue mission.

Members of the 8th SOS were involved in those plans. In fact, some

of the same crew members who participated in Eagle Claw came back and started preparing for the follow-up mission.

Healing

the wounds

At the same time, the squadron needed to bury its dead, and start healing the wounds from Desert One. Beyers

survived the tragedy. After spending a year in the hospital, and enduring 11 surgeries, he was medically separated from the

Air Force.

The bodies of the eight men were eventually returned to the United

States, and a memorial service was held at Arlington National Cemetery.

Memories of that ceremony are still vivid for many of the rescue

team. Weaver, who was an escort officer, still recalls when President Carter visited the families prior to the service. After

talking with a Marine family, the president made his way to the family Weaver was escorting.

“He came up to the family, then he looked down at those two

little boys, and he just got down on his knees and wrapped his arms around them,” Weaver said. “Tears were streaming

down his cheeks. Here’s the president of the United States, on his knees, crying, holding these boys. That burned right

in there,” he said pointing to his chest.

A memorial was placed at Arlington National Cemetery honoring the

eight men killed. Subsequently, other tributes have been made remembering the men who died at Desert One. Hurlburt has dedicated

streets in their honor. New Mexico’s Holloman Air Force Base Airman Leadership School is named for Tech. Sgt. Joel Mayo,

the C-130 flight engineer killed at Desert One.

Mayo and Sanchez were good friends. “I talked to him that

night,” Sanchez said, flashing back to a time long ago. “It’s important people understand. Joel had no idea

he was going to give his life that night. But, if you told him he was going to die, he still would’ve gone.”

Sanchez’s words capture the essence of every man on the mission.

They were a brave, courageous group of men, attempting the impossible, for a noble and worthy cause. They came up short and

have lived 21 years with the demons, or gremlins, that sabotaged their mission of mercy.

“They tried, and that was important,” said Col. Thomas

Schaefer, the U.S. Embassy defense attaché and one of the hostages. “It’s tragic eight men died, but it’s

important America had the courage to attempt the rescue.”

In his living room, Beyers gazes at the photos on his wall. Pointing

to the picture of his crew, he says, “How I survived and they didn’t, I don’t know. I was lucky.”

Even having lived so long with the horrible outcome of that mission,

Beyers never doubts his choice to take part.

“We do things other people can’t do,” he said.

“We would rather get killed than fail. It was an accident. But, I have no doubt, had the Army guys gotten in there,

we would’ve succeeded.”

It comes down to that. Desert One is a story of what could’ve

been.

|

by Col. J.V.O. Weaver

J.V.O. Weaver and Hal Lewis had been friends for years and had

flown together countless times. But, when Weaver went to shake Lewis’ hand before the two departed Masirah, Oman, on

April 24, 1980, Lewis’ words stopped Weaver dead in his tracks. “J.V.O. this is going to be bad,” Weaver

remembers his friend saying. “Someone is not coming back from this.” Weaver shot this picture of a C-130 Hercules

taxiing out of Masirah before boarding his own plane en route to Desert One. Lewis’ premonition proved right —

five airmen and three Marines died at Desert One. |

| Remembering heroes |

April 2001 |

| Eight men died during the aborted attempt to rescue

American hostages held captive in Iran. Five of them were airmen from the 8th Special Operations Squadron at Hurlburt Field,

Fla. Three were Marine helicopter crewmen.

“Take solace in the fact [that] what they did only a few

could even attempt,” said Lt. Gen. Norton Schwartz, the commander of Alaskan Command, at a 20th anniversary commemorative

ceremony at Hurlburt Field, Fla. “What they did was keep the promise. They had the guts to try.”

Schwartz was a pilot in the 8th SOS at the time of the rescue mission

and went on to command Hurlburt’s 16th Special Operations Wing.

Another special operator and now chairman of the Joint Chiefs of

Staff, Gen. Hugh Shelton, expressed similar sentiments during a speech at an April 2000 ceremony at Arlington National Cemetery

honoring those killed.

“The sheer audacity of the mission, the enormity of the task,

the political situation at the time. When I reflect on the results — both positive and negative — I’m awed,”

Shelton said.

“The very soul of any nation is its heroes. We are in the

company of giants and in the shadow of eight true heroes,” he said.

Those heroes are Capt. Richard L. Bakke, 33; Capt. Harold J. Lewis,

35; Capt. Lyn D. McIntosh, 33; Capt. James T. McMillan II, 28; Tech. Sgt. Joel C. Mayo, 34; Marine Staff Sgt. Dewey L. Johnson,

31; Marine Sgt. John D. Harvey, 21; and Marine Cpl. George N. Holmes Jr., 22.

— Master Sgt. Jim Greeley |

| Desert One |

April 2001 |

|

DOD Archive Photo

The five members of Hurlburt Field’s 8th Special Operations

Squadron who were killed at Desert One were remembered at a memorial service at the base’s air park two weeks after

the accident. “It’s tragic eight men died, but it’s important America had the courage to attempt the rescue,”

said retired Col. Thomas Schaefer, U.S. Embassy defense attaché and one of the hostages. |

|