|

The Hostages and The Casualties

Sixty-six Americans were taken captive when Iranian militants seized the U.S. Embassy in Tehran on Nov. 4, 1979, including

three who were at the Iranian Foreign Ministry. Six more Americans escaped. Of the 66 who were taken hostage, 13 were released

on Nov. 19 and 20, 1979; one was released on July 11, 1980, and the remaining 52 were released on Jan. 20, 1981. Ages in this

list are at the time of release.

The 52:

Thomas L. Ahern, Jr., 48, McLean, VA. Narcotics control officer.

Clair Cortland Barnes, 35, Falls Church, VA. Communications

specialist.

William E. Belk, 44, West Columbia, SC. Communications and records officer.

Robert O. Blucker, 54, North

Little Rock, AR. Economics officer specializing in oil.

Donald J. Cooke, 26, Memphis, TN. Vice consul.

William J. Daugherty,

33, Tulsa, OK. Third secretary of U.S. mission.

Lt. Cmdr. Robert Englemann, 34, Hurst, TX. Naval attaché.

Sgt. William

Gallegos, 22, Pueblo, CO. Marine guard.

Bruce W. German, 44, Rockville, MD. Budget officer.

Duane L. Gillette, 24, Columbia,

PA. Navy communications and intelligence specialist.

Alan B. Golancinksi, 30, Silver Spring, MD. Security officer.

John

E. Graves, 53, Reston, VA. Public affairs officer.

Joseph M. Hall, 32, Elyria, OH. Military attaché with warrant officer

rank.

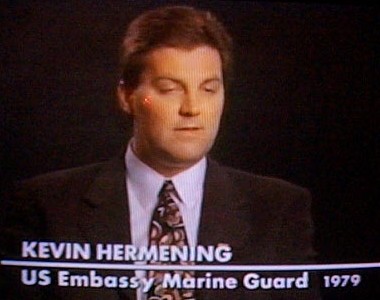

Sgt. Kevin J. Hermening, 21, Oak Creek, WI. Marine guard.

Sgt. 1st Class Donald R. Hohman, 38, Frankfurt, West

Germany. Army medic.

Col. Leland J. Holland, 53, Laurel, MD. Military attaché.

Michael Howland, 34, Alexandria, VA.

Security aide, one of three held in Iranian Foreign Ministry.

Charles A. Jones, Jr., 40, Communications specialist and

teletype operator. Only African-American hostage not released in

November

1979.

Malcolm Kalp, 42, Fairfax, VA. Position unknown.

Moorhead C. Kennedy Jr., 50, Washington, DC. Economic and commercial

officer.

William F. Keough, Jr., 50, Brookline, MA. Superintendent of American School in Islamabad, Pakistan, visiting

Tehran at time of embassy

seizure.

Cpl. Steven W. Kirtley, 22, Little

Rock, AR. Marine guard.

Kathryn L. Koob, 42, Fairfax, VA. Embassy cultural officer; one of two women hostages.

Frederick

Lee Kupke, 34, Francesville, IN. Communications officer and electronics specialist.

L. Bruce Laingen, 58, Bethesda, MD.

Chargé d'affaires. One of three held in Iranian Foreign Ministry.

Steven Lauterbach, 29, North Dayton, OH. Administrative

officer.

Gary E. Lee, 37, Falls Church, VA. Administrative officer.

Sgt. Paul Edward Lewis, 23, Homer, IL. Marine guard.

John

W. Limbert, Jr., 37, Washington, DC. Political officer.

Sgt. James M. Lopez, 22, Globe, AZ. Marine guard.

Sgt. John

D. McKeel, Jr., 27, Balch Springs, TX. Marine guard.

Michael J. Metrinko, 34, Olyphant, PA. Political officer.

Jerry

J. Miele, 42, Mt. Pleasant, PA. Communications officer.

Staff Sgt. Michael E. Moeller, 31, Quantico, VA. Head of Marine

guard unit.

Bert C. Moore, 45, Mount Vernon, OH. Counselor for administration.

Richard H. Morefield, 51, San Diego,

CA. U.S. Consul General in Tehran.

Capt. Paul M. Needham, Jr., 30, Bellevue, NE. Air Force logistics staff officer.

Robert

C. Ode, 65, Sun City, AZ. Retired Foreign Service officer on temporary duty in Tehran.

Sgt. Gregory A. Persinger, 23, Seaford,

DE. Marine guard.

Jerry Plotkin, 45, Sherman Oaks, CA. Private businessman visiting Tehran.

MSgt. Regis Ragan, 38, Johnstown,

PA. Army noncom, assigned to defense attaché's officer.

Lt. Col. David M. Roeder, 41, Alexandria, VA. Deputy Air Force

attaché.

Barry M. Rosen, 36, Brooklyn, NY. Press attaché.

William B. Royer, Jr., 49, Houston, TX. Assistant director

of Iran-American Society.

Col. Thomas E. Schaefer, 50, Tacoma, WA. Air Force attaché.

Col. Charles W. Scott, 48, Stone

Mountain, GA. Army officer, military attaché.

Cmdr. Donald A. Sharer, 40, Chesapeake, VA. Naval air attaché.

Sgt. Rodney

V. (Rocky) Sickmann, 22, Krakow, MO. Marine Guard.

Staff Sgt. Joseph Subic, Jr., 23, Redford Township, MI. Military policeman

(Army) on defense attaché's staff.

Elizabeth Ann Swift, 40, Washington, DC. Chief of embassy's political section; one of

two women hostages.

Victor L. Tomseth, 39, Springfield, OR. Senior political officer; one of three held in Iranian Foreign

Ministry.

Phillip R. Ward, 40, Culpeper, VA. Administrative officer.

One hostage was freed July 11, 1980, because of an illness later diagnosed as multiple sclerosis:

Richard I. Queen, 28, New York, NY. Vice consul.

Six American diplomats avoided capture when the embassy was seized. For three months they were sheltered at

the Canadian and Swedish embassies in Tehran. On Jan. 28, 1980, they fled Iran using Canadian passports:

Robert Anders, 34, Port Charlotte, FL. Consular officer.

Mark J. Lijek, 29, Falls Church, VA. Consular officer.

Cora

A. Lijek, 25, Falls Church, VA. Consular assistant.

Henry L. Schatz, 31, Coeur d'Alene, ID. Agriculture attaché.

Joseph

D. Stafford, 29, Crossville, TN. Consular officer.

Kathleen F. Stafford, 28, Crossville, TN. Consular assistant.

Thirteen women and African-Americans among the Americans who were seized at the embassy were released on Nov.

19 and 20, 1979:

Kathy Gross, 22, Cambridge Springs, PA. Secretary.

Sgt. James Hughes, 30, Langley Air Force Base, VA. Air Force administrative

manager.

Lillian Johnson, 32, Elmont, NY. Secretary.

Sgt. Ladell Maples, 23, Earle, AR. Marine guard.

Elizabeth Montagne,

42, Calumet City, IL. Secretary.

Sgt. William Quarles, 23, Washington, DC. Marine guard.

Lloyd Rollins, 40, Alexandria,

VA. Administrative officer.

Capt. Neal (Terry) Robinson, 30, Houston, TX. Administrative officer.

Terri Tedford, 24,

South San Francisco, CA. Secretary.

Sgt. Joseph Vincent, 42, New Orleans, LA. Air Force administrative manager.

Sgt.

David Walker, 25, Hampton, TX. Marine guard.

Joan Walsh, 33, Ogden, UT. Secretary.

Cpl. Wesley Williams, 24, Albany,

NY. Marine guard.

Eight U.S. servicemen from the all-volunteer Joint Special Operations Group were killed in the Great Salt Desert

near Tabas, Iran, on April 25, 1980, in the aborted attempt to rescue the American hostages:

Capt. Richard L. Bakke, 34, Long Beach, CA. Air Force.

Sgt. John D. Harvey, 21, Roanoke, VA. Marine Corps.

Cpl.

George N. Holmes, Jr., 22, Pine Bluff, AR. Marine Corps.

Staff Sgt. Dewey L. Johnson, 32, Jacksonville, NC. Marine Corps.

Capt.

Harold L. Lewis, 35, Mansfield, CT. Air Force.

Tech. Sgt. Joel C. Mayo, 34, Bonifay, FL. Air Force.

Capt. Lynn D. McIntosh,

33, Valdosta, GA. Air Force.

Capt. Charles T. McMillan II, 28, Corrytown, TN. Air Force.

This list was adapted from information in Free At Last by Doyle McManus.

The Hostages Finally Arrive Home in the United States!

The following is an excerpt from the Tuscon Weekly

"Hostages

Reveal Iran Torture.

"The emancipated hostages told of beatings and other atrocities at the hands of the Iranian

captors today as they telephoned their loved ones back home.

"One said ... he was told by Iranian interrogators

... that his mother had died. He didn't learn that she was still alive until the freed captives reached Germany this morning.

"As they began a stay of several days at a U.S. military hospital in Wiesbaden, Germany, most of the 52 hostages

talked with their families for the first time in 445 days. ...

"Col. Leland Holland, 53, security chief of

the U.S. Embassy in Tehran ... 'spent a month in what he called the

"dungeon" and said his captors were S.O.B.s,'

said the colonel's mother. 'He said his house was ransacked and

everything taken, including his watch and rings. They

took all the furniture and clothes.'

"A spokesman for the family (of Duane 'Sam' Gillette) said: 'His treatment

was at times disgusting. I think President

Reagan was polite when he termed the Iranians barbarians. We know that his

letters were covering up what the real

situation was. There was no physical torture, but there was psychological pressure.

The food wasn't good and the

conditions were very poor.'

"And the family of Malcolm Kalp said ... 'He

told us he was beaten by them and placed in solitary confinement because of his escape attempts.' He served from 150 to 170

days in solitary. ...

"Returnee David Roeder, 40, of Washington, D.C., said, 'I've never been so proud to

be an American in all my life.' ...

"Outside the hospital ... the crowd ... broke into a chant of 'U.S.A., U.S.A.'

Only 12 hours and nine minutes earlier, the two women and 50 men hostages flew out of Iran on an Algerian jet to the Islamic

Revolutionary Guards' jeers of 'Down with America' and 'Down with Reagan.' ... "

Click here to go to the original web site of this next article

Iowan drew on faith during hostage ordeal

Posted March 13, 1999

By James Q. Lynch

Gazette

Northeast Iowa Bureau

WAVERLY -- The 444 days she spent as a hostage in Iran may define Kathryn Koob in the eyes

of others, but she doesn't think of the ordeal often.

"I think about it when I'm asked," she said at

a press conference Friday at Wartburg College. "It's a part of my life."

She has been able to move on

from the hostage experience that began almost 20 years ago because her faith allowed her to cope with the situation at the

time, Koob said. Isolated from the 50 other hostages, she drew on the faith she learned growing up in an "orthodox Lutheran"

household in Eastern Iowa.

"Without that faith, I don't know what I would have done," Koob said. "It

never occurred to me not to use that faith, the strength that I had been told would be there when I needed it."

She accepted her captivity as a challenge, "something I could not change, but had to learn to live with."

"I didn't like it, but told myself that with the help of God I'll get past it," she said.

As

a result, Koob said, she was able to leave her anger behind in Iran along with her ice skates and some of her favorite recordings.

In spite of her experience there, Koob is encouraged by diplomatic efforts to re-establish links between Iran and

the West.

Apart from a visit to the United Nations last year, Iranian President Mohammad Khatami's visit to Italy

this week was the first an Iranian leader has made to a Western nation since the 1979 Islamic revolution installed the rule

of the clergy in the country.

Student leaders of that revolution took control of the U.S. Embassy in Tehran in

November 1979 and held Koob and her colleagues hostage.

"I had hoped we could recognize our differences even

sooner," she said about the diplomatic efforts. "But perhaps slower is better.

"However angry we

might be about the hostage crisis, Iran is a country full of wonderful people, intellect and culture, and should be a part

of the world community," Koob added.

Terrorists still take hostages, but Koob came to Wartburg in Waverly,

where she now lives, to talk about other forms of terrorism. She spoke at her alma mater on "Terrorism: Antecedents

and Present Action."

"What we're looking at now is narco-terrorism, bio-terrorism, cyber-terrorism and

nuclear terrorism," she said. "In these cases, the threat is the terror.

"There is much more reason

to be worried about bio-terrorism than even a small group of terrorists with a bomb," she said. "The threat is

much, much larger."

She called on federal, state and local governments to prepare responses to these new forms

of terrorism. The same resources and effort applied to studying nuclear war scenarios must be applied to preparing to respond

to the new threats of terrorism, she said.

Click here for the original web site of the next article

The Daily Princetonian

Monday, October 18, 1999

Founded 1879 - Online since 1997 Kennedy '52 relates details

of months as hostage in Iran

By KATY ZANDY

Imagine spending 444 days wondering every waking moment whether

or not you would live another hour. For Moorhead Kennedy '52, this nightmarish scenario became a reality in 1979.

Kennedy spoke last night about his experience as a U.S. embassy employee during the Iran hostage crisis as a part of the

'02-'52 lecture series.

In the speech, he described the final days before a group of young Iranians stormed the

embassy compound in Tehran, his days of captivity and a few of his thoughts in hindsight.

Kennedy was introduced

to an audience of about 90 in the Rockefeller College common room by his classmate, Hal Saunders '52, who was assistant secretary

of state at the time of the crisis. Kennedy's wife, Louisa Kennedy, also added her perspective on the experience.

Cut off Saunders described hearing the final words in Washington from embassy officials before contact was cut off – "we're

going down now" – and defended the decision to not pull personnel out of Iran before the crisis.

Following

him, Kennedy said, "The decisions that Hal and his superiors made were not all perfect, but they worked, and the proof

is that you now have a speaker."

Kennedy related the apprehension that he felt in the days before the crisis,

as the embassy began to realize that a serious conflict was almost upon them.

In particular, Kennedy recalled

the prediction he heard just before the crisis from a Marine guard at the embassy. "Man, we're going to have an Alamo,"

the soldier said.

Kennedy went on to describe the denial that he experienced during the early stages of being a

hostage. He slept in one bed with two other men, wearing his suit jacket and tie because he believed that he would be released

any minute.

His wife echoed his initial feeling of denial. "In any crisis, you're going to find a moment

where you accept it. If you're wise, you find ways to normalize it. This took time for the families to get used to,"

she said.

In reaction to the crisis, she volunteered for the State Department and formed the Family Liaison Action

Group, which raised money for medical and psychiatric help for the families of the hostages.

After Kennedy spoke

about her experience during the crisis, her husband finished the story of his captivity – replete with its moments of terror.

"When you are overcome with fear, your legs begin to twitch," he said. "You live on every thread

of evidence, often wrong, and often reaching the worst conclusion."

At the beginning of his captivity, Kennedy

said he was held in the American embassy in Tehran. However, after President Jimmy Carter ordered a helicopter rescue that

ended in failure, the hostages were spread out over the country.

There was a long period of waiting after the

rescue attempt where he was moved frequently, but saw little progress toward a resolution. Finally, a guard walked into

Kennedy's room and said, "OK, let's go."

"Our hearts stopped," Kennedy recalled. "We said,

'Go where?' And he said, 'Home.' "

This is a photo of what the Iranians did to the dead Americans who took part in the rescue attempt. This is a

shot of an Iranian man taking his knife to one of the bodies. He eventually took off the head of the dead

American. This is a barbaric act, but it is not as crude as the next photo, taken of someone who is supposed to

represent the religion of Islam.

This is a photo of someone who was supposed to be a holy man in Islam. His name is Ayatollah Kalkali. He literally spit on

the bodies of our Marines and Airmen that died in Desert One in the attempt. I consider him a criminal, too.

Click on the link to proceed to the original web site for the next article

CAN IRAN BE FORGIVEN?

A dramatic meeting between a former American hostage and one of his captors could be a powerful

symbol of reconciliation

By SCOTT MACLEOD

It has been almost 19 years, but the images from Tehran are

forever burned into the American psyche. The sudden assault on the U.S. embassy by Iranian students. The angry street mobs

shouting "Death to America!" The parades of helpless, blindfolded hostages. Back home, outraged Americans could

only imagine the horrors that the 52 prisoners faced during their 444 days of captivity. Barry Rosen did not have to imagine.

He was there. As the embassy's press officer in 1979, he was not only taken hostage at gunpoint but also accused of leading

a spy ring and subjected to a mock trial. His punishment included months in a barren prison cell, where an always burning

light bulb and constant stress made it almost impossible for him to sleep.

The American government has never forgiven

Iran for what happened, so why should the hostages? But rather than carry resentment around for the rest of his life, Rosen

has decided to make a remarkable gesture of reconciliation. This Friday at a conference in a U.N. building in Paris, he will

come face to face with Abbas Abdi, one of the dozen student leaders who planned and directed the hostage taking. As the dramatic

meeting unfolds, the former hostage and his former captor will give talks on U.S.-Iranian relations, sit down for meals together

and probably even shake hands. That powerful image of healing is sure to be criticized by hard-liners in Iran and by many

Americans, perhaps including other ex-hostages. Both men are attending as private citizens and do not represent their governments

or any groups.

In interviews conducted by TIME with Rosen in New York City and Abdi in Tehran, they said they were

encouraged to meet after Iranian President Mohammed Khatami's call last January--quickly taken up by President Clinton--for

cultural exchanges aimed at bringing down the "wall of mistrust" between their two nations. The idea for the meeting

originated with Iranian moderates who were friends of Abdi's. They approached a Cyprus-based human-rights group called the

Center for World Dialogue, which organized the conference and invited Rosen. Although the two men are still poles apart in

their thinking, they welcomed the chance to put the past behind them and help their countries build fresh ties. "I am

not naive about Iran, but I think it is important to understand one another's feelings," says Rosen, 54, director of

public affairs for Teachers College, Columbia University, in New York City. "I don't have to forgive and forget. But

we are trying to restart this relationship, and this is an important beginning." Agrees Abdi, 42, a columnist for Salam,

a Tehran newspaper: "The aim is to contribute to a better understanding and promote a normalization of relations."

That is easier said than done.

Plans for a London meeting were aborted when British authorities refused Abdi a visa.

He has had to make his preparations in utmost secrecy lest Iran's still powerful hard-liners detain him before his departure

for France. Once a fervent supporter of Iran's clerical regime, Abdi was arrested in 1993 and spent nearly a year in prison

for criticizing the mullahs' aversion to democracy. Rosen has had to overcome his own concerns. Will a public reconciliation

with Abdi create a backlash in Iran against the rapprochement that Rosen deeply hopes for? Or will Abdi somehow publicly

embarrass him? While Abdi is ready to shake hands, Rosen is reluctant to commit himself until the moment comes. He hopes,

though, that his meeting with Abdi will help "close the circle, close that 444 days." That would bring Rosen closer

to a country he loved--and still loves, despite his hostage ordeal.

He first went to Iran as a Peace Corps volunteer

in 1967 before taking up graduate studies in Iranian culture at Columbia University three years later. He became U.S. embassy

press attache in Tehran in 1978, at the height of the revolution that overthrew the Shah. And he was in the embassy on Nov.

4, 1979, when bearded militants poured over the compound's walls and began the 15-month hostage crisis.

Among those

militants was Abdi. In an interview at his spare Tehran office a few blocks from the old U.S. embassy--now a school for the

Revolutionary Guards--the Iranian provided rare insight into the takeover and his role in it. The students' aim was to force

the U.S. government to extradite the deposed Shah. They genuinely feared, Abdi insists, that the Shah's arrival in New York

City in 1979 for medical treatment was part of a U.S. plot to restore him to power, as was done by a CIA-engineered coup

d'etat in 1953. Abdi denies that Ayatullah Khomeini ordered the embassy seizure or knew about it beforehand. "The way

we saw it, the Imam would either approve of the action afterward or disapprove of it, in which case we would have left the

embassy," says Abdi. At 7 a.m. on takeover day, Abdi held a secret meeting with 130 students he had summoned to a hall

at Tehran Polytechnic University, where he was leader of the Organization of Islamic Students. He described the takeover

plans, gave out assignments and ID badges and told the students to head, one by one, to the embassy, where they would meet

up with recruits from other universities. As hundreds thronged into the compound, Abdi's task was to seize the embassy's

visa offices while others handled the main building and the ambassador's residence. According to Abdi, the restraint shown

by U.S. Marine guards may have averted a bloodbath. Had they shot and killed any of the students, he says, he and other leaders

planned to depart and leave the compound to be engulfed by the mob.

Abdi says he never guarded the hostages and

has no recollection of meeting Rosen personally. The Iranian still justifies taking the prisoners as a defense against a

potential U.S.-backed coup d'etat, holds American support for a despotic ruler partly responsible for provoking the students

and tends to downplay the ill treatment of the hostages. However, Abdi echoes the conciliatory words spoken by President

Khatami. "No one likes hurting others," Abdi says. "The Iranians regret what the hostages and their relatives

endured." He adds that he can understand why Americans felt that hostage taking was wrong.

Rosen flatly rejects

the notion that the students' ends justified the means: "It is very dangerous when you cross that moral line."

But he sympathizes with Iranian complaints about U.S. support of the Shah's repressive regime. "There is a moral and

ethical question that Americans have to face up to," Rosen says. "The Shah served the purpose of stability in the

region. But we should have been much more aware of and sensitive to what was going on inside Iran, whether it was human-rights

violations or lack of political growth." If that sort of exchange is heard this week in Paris, conference director Eric

Rouleau will judge the gathering a success. "We thought this meeting could contribute to a better understanding,"

says Rouleau, who witnessed the hostage crisis firsthand as a correspondent for the French daily Le Monde. "There are

people in both countries who would like to turn a page of history, a page that was very painful." Rosen and Abdi may

already have begun writing the next chapter.

--With reporting

by Henry Schuster/CNN web site address :

http://www.time.com/time/magazine/1998/dom/980803/world.can_iran_be_forgiv10.htm l

Click on the link to the original web site for the next article.

Former U.S. hostage meets his Iranian captor

Men shake hands, look to future

July 31, 1998

Web posted

at: 11:56 p.m. EDT (2356 GMT)

In this story:

No apologies

Protesters disrupt meeting

Related

stories and sites

PARIS (CNN) -- Almost 20 years after an Islamic revolution overthrew the U.S.-backed government

in Iran, a former U.S. Embassy hostage met face-to-face with one of his Iranian captors.

From 1979 to 1981, Barry

Rosen and 51 other U.S. citizens were held captive for 444 days by Iranian militant students upset over the U.S. decision

to allow deposed Iranian leader Shah Mohamed Reza Pahlavi, who had cancer and other ailments, to enter the United States for

medical treatment.

Other embassy occupants captured when the students stormed the building were released not long

after the takeover.

On Friday, Rosen shook hands with Abbas Abdi, who helped organize the embassy seizure. Their

meeting was organized by the Cyprus-based Center for World Dialogue as part of a three-hour meeting on U.S.-Iranian relations.

Rosen, 54, said the decision to meet with his former captor was one of the toughest he ever made.

"But this

platform is not for remembering only my pain or blows to American honor," he said. "Iranians also suffered deeply."

No apologies

Abdi said the students thought the takeover on November 4, 1979, would last no more than

a week. The hostages were freed on January 21, 1981. He called the occupation "the most nonviolent possible measure taken

... in response to what the United States had done."

Abdi, 42, now a senior editor at the previously hard-line

newspaper Salaam, acknowledged that he was among those who planned the event.

"I could be taken hostage

for 444 days," Abdi said. "This I could overlook. "But taking a nation hostage for 25 years," he said,

"needs more apologies."

The hostage crisis was but "a row of bricks in this tall wall (of mistrust),"

Abdi said. He said the wall's foundation was laid in 1953, with the U.S.-backed coup that toppled President

Mohamed Mossaddegh and returned the shah to the Peacock Throne. Rosen disagreed.

"No

matter how they rationalize, however, they must face up to the wrong and admit, if only to themselves,

that it was unjustified," he said.

In the end, no apologies were given, but the men shook hands and agreed

to look toward the future.

"I'm here with Mr. Abdi, because I want to see Americans and Iranians

turn that difficult corner away from mutual demonizing," Rosen said.

"The past cannot be altered,"

said Abdi. "Instead, we must focus on the years ahead and endeavor to build a better future," he said.

Protesters

disrupt meeting

The hostage crisis remains a sensitive issue, even among Iranians. The start of the session

was interrupted by two Iranian exiles who denounced Abdi as a "mass murderer" and a "terrorist." Both

men were forcibly removed from the hall.

Official Iranian attitudes toward the United States have softened somewhat

since the election last year of Iranian President Mohammad Khatami.

Despite opposition from hard-liners in Tehran,

Khatami has called for a "crack in the wall of mistrust" between both countries.

There was no immediate official response from Iran about Friday's meeting. However, the U.S. State

Department called the encounter "a positive development in the people-to- people dialogue that

both nations support."

The Associated Press contributed to this report.

October 26, 2004

Q&A: Kevin Hermening on the Iran Hostage Crisis

Nov. 4 will mark the 25th anniversary of the start of the Iran Hostage Crisis – a day when Iranian

extremists and militants seized the U.S. Embassy in Tehran and captured several dozen U.S.

diplomats, servicemen and civilians and began a 444-day siege that captivated Americans and the world.

During that 444 days, Walter Cronkite closed each of his broadcasts by counting the number of days the Iranians

– led by extremist religious leader Ayatollah Khomeini – held U.S. citizens in violation

of international law. Ted Koppel also began a nightly broadcast, then called “America Held Hostage,” which later

transformed into “Nightline.” Eight U.S. servicemen died in an aborted rescue attempt,

Operation Eagle Claw, that ended unsuccessfully in a fiery crash in the Iranian desert.

The crisis, many believe, paralyzed the administration of President Jimmy Carter and led to his defeat at

the hands of Ronald Reagan in 1980. The hostages were finally released on the day Reagan was inaugurated.

Command Post contributor Ed Moltzen interviewed the youngest of the 52 hostages who had been held for that

period, Kevin Hermening, who at the time was a 20-year old Marine assigned to guard the Tehran embassy. Since 1981, Hermening

has become active civically in Wisconsin, becoming a school board and twice running unsuccessfully for U.S.

Congress as a Republican.

CP: Does it seem like 25 years ago?

Hermening: From my perspective, there is so much that has occurred in my life since then.

It rarely is given a second thought by me. It doesn’t mean that it’s ignored – especially in the context

of current events. Obviously there are a lot of current events that have affected the way that our country has – and

in many aspects hasn’t – dealt with the threat of state-sponsored terrorism.

CP: What are your most vivid memories of your time being held against your will by the

Iranian students?

Hermening: Probably the uncertainty of knowing how it would all end, or if it would come

to an end. There was so much emotion and drama and trauma during that time. Of course, the Soviets had invaded Afghanistan,

the Iraq-Iran war began. There was the failed attempt to rescue us, resulting in the deaths of eight men who perished in the

Iranian desert.

CP: Being a marine, did it make it more difficult for you?

Hermening: There were many aspects of it - including being young - that were involved.

There was an element of adventure and excitement surrounding it. It doesn’t mean we were any less fearful. But when

you’re 20 years old and you’ve been through military training you kind of feel invincible. How quickly that false

image is shattered. Bravado is important, but only if it doesn’t result in your getting yourself foolishly killed. I

tried to escape once – I never really had an opportunity later – that resulted in 43 days in solitary confinement.

CP: Hostage and then-CIA agent William Daugherty wrote a book two years ago in which he describes 444 days of mostly solitary confinement, and suggested he and the other military personnel

taken hostage had it worse out of any Americans. Were you mistreated?

Hermening: After the failed escape attempt by a few of us, about a week later they had

a mock execution that occurred in which they stormed into our rooms in the middle of the night, strip searched us and had

us standing out in the hallway. Some of the most radical elements ran up and down in the hallway – we were spread eagle

– and they were shouting out execution commands at the top of their lungs.

Meanwhile, others were in our rooms searching out for anything we may have had, including weapons. Although

we know now anything can be a weapon.

CP: How did you plan the escape?

Hermening: Joe Subic, Steven Lauterbach and I – in my case, I never made it out of the room. They

had taken us to a different building for showers. They put me into the only room in the ambassador’s residence that

was a safe-room….I never made it out of the room. They immediately handcuffed me and put me into another room, in which

I was put into solitary. Five feet by ten feet.*

CP: Were you able to form a bond, or friendships, with any of the other U.S.

diplomats and civilians that lasts today?

Hermening: Alan Golancinksi was one. Don Cooke and I, we kind of became friends for the

short time we were together. I was roommates with Alan right after I got out of solitary. That was a real relief to me to

get out of solitary confinement. Some of the other guys in Vietnam who were in POW camps for seven

years – my experience pales in comparison. It doesn’t mean it was easy, but I would never try to suggest our (situations)

were similar.

CP: You’ve spoken of your admiration for Ronald Reagan and your opportunities to

meet him. But some hostages, in returning from Iran, have said they were measurably cooler toward President Carter –

whom you also met after you were freed. What’s your assessment of Carter?

Hermening: I would describe it that way, too. But for me, it was in my pre-political days…I

would describe it – there was a cool reception given to him. For me, I would describe it as being honored to meet a

president. I do think that President Carter is one of our best ex-presidents, though I would describe his presidency as a

failed presidency. I fail, personally, to see the merits of putting the interests of 52 individuals ahead of the nation’s

national security. I really do believe our situation was one of the first terrorist acts in a series that have victimized

Americans worldwide. I would further say that when President Carter agreed to return $9 billion of frozen Iranian assets to

the terrorist government under the Ayatollah Khomeini, as Charles Scott said, Iran walked away with no cost in blood or treasure.

In essence, the terrorist organizations, those who put a face on terrorism – al Qaeda, Hamas and others – they

get their support from governments. By not extracting a penalty, or anything punitive, I think it simply encouraged more acts

against Americans.

CP: Looking at Iran today, some of the students who took over the U.S.

embassy are now in positions of power, including Tehran Mary – who is an Iranian vice president – and one

of the leaders who the New York Times has even described as a reformer…

Hermening: I just read recently that some are in the government, some are in the opposition

– today – and some are in prison. That’s, in my opinion, what you get when you look at a group of anarchists

which is really what terrorism is. Anarchy.

CP: Many of the same people who took you hostage are now seeking to expand a nuclear program

for Iran. Is this something that angers you? What are your thoughts?

Hermening: That should scare the heck out of every American and anybody in the West and,

I would submit, their Muslim neighbors. The other thing lost in the broader context is, that Iranians are not Arabs. Except

or Israel and Iran, every other country over there is Arab or Arabic. Iranians are Aryans. Despite their common interest in

a religious background, Islam, they do not share a cultural connection. Hence the acrimonious relationship between Iraq and

Iran and some of their neighbors to the east. I was one of the few people I know, I think, who understood why (Gen. Norman)

Schwarzkopf and Colin Powell decided not to take out Saddam in 1991. We weren’t prepared to deal with, as a country,

militarily or diplomatically, creating a vacuum in Iraq where Syria and Iran could consumer that country. And with all the

difficulty this President Bush has had in winning the peace, at least he is willing to fortify the forces. There are 16,000

forces whose job is to protect the oil fields from sabotage. I personally don’t see that as a bad thing.

CP: Do you believe there are enough pragmatists in Iran to ever see a successful reform

movement?

Hermening: I think there are some forces over there that are interested in breaking the

stronghold the mullahs have on their country. I don’t know. They’ve had, I believe, about two dozen government

buildings burned by government protesters in the last two months.

CP: Anyone under the age of 25 – including what could be millions of voters –

weren’t even born yet when you were held captive. If you could have them understand one thing about that time, what

would it be?

Hermening: I think it would have to include what I consider to be a reality: that there

are individuals and entire governments who are so opposed to Western values and freedom that they are willing to use every

means possible to bring about our destruction. Even to the point they are willing to support financially those who are willing

to come into our own country to make us fearful and uncomfortable without our own borders.

CP: Do people still stop you, and ask questions about your experience?

Hermening: It’s become less and less, just by virtue of the fact that I am more active

in other things. I’ve done a lot of public speaking. I speak on Veterans Days and Memorial Days in schools. I make civic

appearances. The sad irony is that people care more about what we had to eat (while being held hostage) and whether I’ve

had any nightmares since I got back – which I haven’t – than they do wondering how did this happen to begin

with, and how can we protect Americans here and abroad in light of what they’re trying to do today?

CP: Yet at the same time, the same holds true in Iran: Anyone under the age of 25 doesn’t

remember what happened back then – they weren’t yet born. How does this work in our favor?

Hermening: I think that there is some hope, because young people do not have a historical

attachment to the Ayatollah Khomeini…

Once you open up the Freedom Genie, the Technology Genie – whether it’s satellite dishes, or

the Internet, I think it’s next to impossible to put it back. And that’s why I personally hold out a great hope

for many of these Middle Eastern nations to become more democratic. Even for China to try to contain what is likely to spread

like wildefire – and that’s economic development and recognition of personal liberties and civil liberties –

I don’t think you can permanently keep that down.

In Iran, it was a very strong sense that the United States was meddling in the internal affairs of their

country. The mullahs were very fortunate. They almost had the perfect storm: the Shah was getting ill, President Carter being

a particularly weak president not standing by our ally, and we left (the Shah) and all of his supporters out to dry. This

is the big concern that somebody like myself would have in a change of the administration in Washington right now. –

would be people like the president of Pakistan, who has really gone out on a limb at the risk of his own political survival

(although he has the iron hand of military power), Musharraf is using (the military) to support the war on terror. If we have

a total reversal of policy, what’s it going to mean for the folks who have gone out on a limb? Personally, I think it’s

going to mean an even more unstable world over time.

I hate to sound like a partisan – even though I am – but I think in the big scheme of thigns

I think it is more in our nation’s advantage to stand for something principled in a part of the world that only understands

force and, I should say, respects strength.

CP: Is there any one solution for the U.S. to have a normal relationship

with Iran?

Hermening: The problem is we are not in the cold war nay more. Countries such as France

and Germany, and some of the more longstanding alliances, play less of an important role to our national security, and our

way of life for that matter, than they once did. After all, 25 years ago and prior to that, most of our international trade

and international exchange students came from largely western countries. Our economic interaction occurred mostly with Western

nations. That’s because that’s where most of the wealth of the world was located…

Egypt and Pakistan play much more of a role to us today. They are the new France and Germany as an example

- economically, politically, culturally perhaps not yet. I don’t think it’s a bad thing for us to have as an objective

to spread freedom around the world.

Posted By Late Final at October 26, 2004 09:28 PM | TrackBack

Ex-Hostages See Terror Roots in 1979 Iran

A Quarter-Century Later, U.S. Hostages See Beginnings of Modern Terrorism

in 1979 Iran

Iranians burn a U.S. flag outside of the former U.S. Embassy in a gathering marking the 25th anniversary of the seizure

of the U.S. Embassy in Tehran, on Wednesday, Nov. 3, 2004.Thousands of Iranian students gathered outside the former American

embassy in Tehran on Wednesday to mark the 25th anniversary of the 1979 storming which led to the year-long "hostage crisis"

between Iran and the United States.(AP Photo/Hasan Sarbakhshian)

McLEAN, Va. Nov 3, 2004 — In the minds of many, terrorists

struck their first blow against the United States on Sept. 11, 2001. But others look back exactly a quarter-century ago, on

Nov. 4, 1979, when 66 Americans were taken hostage at the U.S. Embassy in Iran.

Most remained in captivity for 444 days. Today, reflecting on their experiences

through the prism of 9-11, the war in Iraq and two decades of tumultuous relations with the Middle East, many say the United

States was too late to recognize that a new era had begun.

"The day they took us is the day they should have started the war on terrorism,"

said Rodney "Rocky" Sickmann, 47, of St. Louis County, Mo., an embassy security guard.

Many agree that terrorists were emboldened by their success in the Iran hostage

crisis none of the hostages were killed, but the U.S. government agreed to release $8 billion in frozen Iranian assets and

see the kidnappings and beheadings in Iraq as a consequence.

"Given the terrorist modus operandi nowadays, we probably wouldn't come out

alive. They weren't as bold then. They had a latent fear of the United States," said Chuck Scott, 72, of Jonesboro, Ga., a

former Green Beret in Vietnam who was an Army colonel when he was taken hostage.

Steven Kirtley, 47, of McLean, who was a Marine security guard at the embassy,

said that while he's grateful everybody survived, he's also angry about what he sees as America's largely ineffectual response

to the hostage-takers. He called the episode "a stepping stone to get that terrorist movement going. It was such a terrible

loss of face … such a show of weakness that I still don't think we've recovered."

Fifty-two of the hostages were held for the entire 444 days. Of those, 11

have since died.

Among the rest, memories of that time have resurfaced with the kidnappings

and beheadings of Americans in Iraq.

"When I saw them there blindfolded with the guys with the ski masks on I had

gone through those things in Iran," said Rick Kupke, 57, of Rensselaer, Ind. "I can tell exactly what they felt and the fear

that's going through them."

William Blackburn Royer Jr., 73, of Katy, Texas, remembers being jolted awake

by the screams of his captors, "herded like cattle" into another room, stripped naked and forced up against a wall in front

of a firing squad.

"The whole thing was a shock to the system my legs were shaking from the insecurity

of the situation," he said. "It was intended as a good psychological upheaval."

Still, he was not sure if he would be killed.

"I knew this was a political thing," he said. "Ultimately, I think I thought

that we were too valuable to be disposed of completely. So I kept the faith in that respect. (But) I had my doubts at a couple

points."

Paul Needham said he remembers reciting the 23rd Psalm as he was lined up

for a firing squad. He said he reflects on his captivity every day.

"It definitely changed me," said Needham, 53, of Oakton, Va., a professor

at the National Defense University. "I took a look at getting my priorities in life in order God and family and country, rather

than work, work and work."

While nearly all the hostages said they feared for their lives at some point,

many said their memories center on the tedium. Most hostages were largely isolated, and many said they were allowed outside

for exercise less than once a month.

During a six-week stint in solitary confinement, Gary Earl Lee said he "made

friends" with ants and a salamander that inhabited his room. He would tease the ants with a pistachio nut, letting them almost

reach it before nudging it farther away.

"At least they were something better than the guards," said Lee, a retiree

living in south Texas.

L. Bruce Laingen, of Bethesda, the embassy's charge d'affaires, was the highest

ranking American taken hostage. He said it doesn't make sense that 25 years later the United States has little dialogue with

Iran, considering the large American stake in the Middle East.

He mainly faulted Iranian leaders for pursuing hostile policies such as developing

nuclear technology and continuing to threaten Israel. He has lingering bitterness for the men and women who took him hostage.

But he doesn't blame the Iranian people, who he said were welcoming.

"We need to understand Iran, and Iran needs to seek to understand us," he

said.

Scott said he's still frustrated that the U.S. government has never held Iran

accountable for taking the hostages.

"I agree with the war on terrorism, but the war on terror by the current administration

has been a very selective war. So far we've gone after the really easy targets," said Scott, who opposed going into Iraq but

says America must now remain committed to finishing the job there.

Kirtley, on the other hand, believes America is on the right track with the

war in Iraq and Afghanistan.

"It's the right approach," he said. "That culture responds more to strength

than to a negotiated response."

As for the anniversary, many said they prefer to remember another day.

"We celebrate Jan. 20, the anniversary of our release," Laingen said. "That's

a good day. Nov. 4 is the day the roof fell in."

Associated Press writers Kristen Gelineau in Richmond, Va.; Steve Manning

in College Park, Md.; Russ Bynum in Savannah, Ga.; Carol Druga in Indianapolis and Betsy Taylor in St. Louis contributed to

this report.

Copyright 2005 The Associated Press. All rights reserved.

http://abcnews.go.com/US/wireStory?id=223814&CMP=OTC-RSSFeeds0312

Former Iranian hostage meets with area students

Discusses experiences and repercussuionsKarima Tawfik, Managing Health Editor 11/8/2004 Area high-school students met with Bruce Laingen, former U.S. ambassador to Iran

and hostage during the Iranian hostage crisis of 1979. Laingen, currently President of the American Academy of Diplomacy,

talked with a dozen students, three of them Blazers, at the Dirksen Senate office building on Thursday, November 4,

the 25th anniversary of the crisis. He discussed his experiences as a hostage and the current U.S. relations with Iran. In

response to interview questions, Laingen stated that the act of taking political prisons is "abominable." "Hostage taking

is a fundamental violation of human rights," he said. "The government endorsed the action of Iranian students who had taken

us hostage to use us as pawns for their political gains." Despite the actions of the Iranian government, Laingen said that

the U.S. should be communicating with Iran. "For 25 years we have not talked officially with that consequential region," he

said. Laingen was serving as chargé d'affaires of the American Embassay in Iran when he became one of 53 Americans

captured and held in solitary confinement between November 1979 and January 1981. He describes his experience as a

"debilitating experience." "You can do nothing but look at a bulb hanging from your ceiling," he said. Laingen and his

colleagues were blindfolded when outside of their cells and were threatened by "mock executions," where Iranian militants

pressed guns to their heads. The U.S. embassy was seized by Iranian students during the overthrow of the American-backed

shah regime that had been installed in Iran in the 1950s. Laingen said Iran's anger toward American support for the shah

prompted the hostage crisis. While Laingen said that Iranian actions against him and his colleagues were horrific,

he criticized the Bush administration's rhetoric to describe countries such as Iran and Iraq. "There's no real axis of evil,"

he said. After the overthrow, Ayatollah Khomeini gained power forming a theocratic government. Laigen stressed the

rich history and culture of the people of Iran, stating that the Khomeini regime was "an aberration" of Iran's own national

and Muslim traditions. He spoke about U.S. misunderstandings of Iranian culture. "The American public broadly doesn't understand

the role that the Islamic religion plays in the world out there," he said. http://silverchips.mbhs.edu/inside.php?sid=4238

Iran Hostage Crisis: Revisiting 1979

http://www.foxnews.com/story/0,2933,263990,00.html

Friday , April 06, 2007

By Catherine Herridge

Friday, April 6, 2:33 p.m.

As I write, the British hostage crisis is resolved, but their situation has sparked new questions about the Iranian president

and his possible role in the 1979 takeover of the U.S. embassy in Tehran.

Earlier this week, I told you about Kathryn Koob (rhymes with robe), one of two women held for 444 days in ‘79. This week, I met up with

her in Minneapolis, where she told me an extraordinary story about one of her captors at the embassy … a captor she

believes to be Mahmoud Ahmadinejad.

Kathryn's story is remarkable. She says her faith got her through the terrible days when she was isolated and alone. She

had no idea they had released all of the women at the compound, except two, because she rarely saw anyone else. Like the British,

they were segregated and held in isolation.

"We were tied in chairs, faced the wall, told not to speak to each other and we weren't able to communicate, except maybe

if you walked past someone and pressed their shoulder or something like that,” Koob told me.

Over the next year and a half, the students kept with their new radical beliefs and separated the female hostages from

the rest. Koob was often held in a small 8 x 12 foot room. Some of the female guards were strident and unpredictable.

"My fear was that one of them would do something really foolish and strike out, or that the strain would get too much for

one of my colleagues,” she said.

When Iranian president Mahmoud Ahmadinejad was elected in 2005, about a half dozen former U.S. hostages, like Koob, claimed

he was one of the students.

Koob claims her brush with Ahmadinejad came in the embassy courtyard. It was one of the few times she was allowed to go

outside by her captors — so Koob and the other female hostage pulled up their shirt sleeves to get some sun.

"All of a sudden, this whirlwind of a man came into the courtyard, sort of yelling at us, you know, ‘How dare you

do this, how dare you insult the principals of Islam and show your forearms and your legs, you know you're not supposed to

do that,'" Koob said.

Koob’s view is shared by a former CIA officer William Daugherty, who was among the 66 Americans taken in ‘79.

He was first interviewed just after Ahmadinejad's election, where he told FOX, “I think that's what impressed me more

than anything else, was his looks at us, as though, you know, we really weren't worthy to live. Just, just a deep, intense

personal hatred on his part. And that sort of thing really doesn't leave you."

While Koob’s claims, as well as others, are not shared by all of the former hostages, FOX News has learned that state

department officials began quietly investigating their stories.

State Spokesman Sean McCormack told reporters this week that "there was an effort by the U.S. government to get in contact

with former hostages to determine whether or not President Ahmadinejad was, in fact, one of the hostage-takers, or one of

the people that was involved in questioning them or in any way involved with that whole incident."

U.S. officials tell FOX the questions surrounding the Iranian president have never been resolved, but they do believe he

was part of the student movement. What's new and important here is that this episode seems to upping the ante. One official

told me that there is, "Strong interest in any information about Ahmadinejad and his background — especially that 1979

time frame."

Wednesday, April 4, 3:33 p.m.

In this week's intelligence briefing: Iran, the bomb and the British hostages.

On the surface, there doesn't seem to be a connection between the three — but in the Middle East, from my experience,

nothing happens in a vacuum. A new report this week suggests that Iran may be only two years away from the bomb. Senior U.S.

officials are disputing the report, telling FOX that they don't believe Iran will have the ability to build and deliver a

bomb before 2015.

Frankly, 2015 is not very far away either, but in order to cross that threshold, Iran will have to accomplish several things.

U.S. officials confirm that Iran is making a big push to put more centrifuges into its plant at Natanz. Officially, the

Iranians say it’s for power, but no one in the U.S. intelligence community really believes that. As one U.S. official

told me, it takes more than just hardware to get the bomb: "The Iranians must show that they can operate, run the centrifuges

in sync, and run them efficiently [in order to enrich uranium.]”

Even if they can accomplish that, Iran must work on good detonators and also a means of delivery. This is just a fancy

way of saying that they need the raw materials and the know-how to get the bomb. And that could still take years.

What's the connection to the hostages? On Weekend Live Saturday, we interviewed Kathryn Koob. During the 1979 hostage crisis, she was one of only two American women held for the full 444

days in Tehran. Her theory is that the Iranian regime wants to take the focus off their nuclear program. It's almost like

that old saying, "There is no such thing as bad publicity."

As far as Iran is concerned, the world media, the British and the European union are breathing down their neck about the

hostages. It may be a welcome change from constant scrutiny about their nuclear ambitions.

Koob is now one in a long line of former U.S. hostages who believe with absolute certainty that the Iranian President Mahmoud

Ahmadinejad was one of the students who held them in ‘79 and ‘80. The official line from the intelligence community

is that they know Ahmedinejad was part of the student movement in Iran, but they don't know what his exact role was. A guard?

One of the hostage-takers? None of these are officially being ruled out.

And, Koob says the seizure of the British sailors has Ahmadinejad's fingerprints all over it.

Catherine Herridge is the Homeland Defense Correspondent for FOX News and hosts FOX News Live Saturday 12-2 p.m. ET. Since coming to FOX in 1996 as a London-based correspondent, she has since reported on

the 2004 presidential elections, Operation Iraqi Freedom, Medicare fraud, prescription drug abuse and child prostitution.

You can read the rest of her bio here.

A First Tour Like No Other

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Held Hostage in Iran

William J. Daugherty

COPYRIGHT 1996 by William J. Daugherty

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

I do not recall now the exact circumstances in which I was finally and firmly offered Tehran for a first tour, nor even

who made the offer. I do know, though, that I did not hesitate a second to say yes. For the most part, I have not regretted

that decision, but at times it is only with a prodigious dose of hindsight that I have been able to keep it in perspective.

After all, it is not often that a newly minted case officer in the CIA's Directorate of Operations (DO) spends his first tour

in jail.

I was recruited into the Agency in 1978, during my last year of graduate school, and I entered on duty the next January.

In my recruitment interviews, I was told about a special program managed by the DO's Career Management Staff that was designed

to place a few selected first-tour officers overseas in a minimal period of time, without lengthy exposure to the Washington

fishbowl or reliance on light cover. The program sounded fine to me, and so I joined the Agency and was rushed through the

Career Training (DO) spends his first tour in jail.

Something else that presented a problem initially--but later came to be a blessing in disguise--was that I enjoyed an

astonishingly small amount of knowledge of the DO and how it did its business. Despite that innocent state, I managed to do

well in training. I was particularly captivated by the stories told by the instructors from the DO's Near East (NE) Division,

and by the challenging situations found in the Middle East; midway through the training course, I had decided I wanted to

go to NE Division. At that point, during a Saturday visit to Headquarters, the deputy chief of NE Division (DC/NE), knowing

of my participation in the special program, raised the possibility of my being assigned to Tehran--even though I possessed

absolutely no academic knowledge of, nor any practical experience whatsoever with, anything Iranian.

By the time of this conversation in spring 1979, Tehran station was in the midst of coping with postrevolutionary Iran.

The Shah (ruling monarch) of Iran had fled the country on 16 January, and soon thereafter--on 2 February--Ayatollah Khomeini

returned from exile in France to oversee a government founded on his perception of an Islamic state. Also of importance to

later events, US Embassy and station personnel had already been taken hostage for several hours, on 14 February 1979, in what

came to be called the St. Valentine's Day Open House.

This last event triggered an almost total drawdown of Embassy and station personnel, along with a reduction of active-duty

American military forces in Iran from about 10,000 to a dozen or so, divided between the Defense Attaché's Office (DAO) and

the Military Assistance Advisory Group (MAAG). It did not, however, generate much (if any) sentiment at the highest levels

of the United States Government for disrupting or breaking diplomatic relations with Iran. In fact, it served mainly to strengthen

American determination to reconcile with Iran's Provisional Revolutionary Government.

By March, Tehran station consisted of several case officers and communicators rotating in and out of Iran on a "temporary

duty" basis. But NE Division was already looking ahead to the time when the station could again be staffed with permanently

assigned personnel and functioning as a station should--recruiting agents and collecting intelligence. And that was the state

of affairs when I met DC/NE in Langley on that spring day.

The Right Background

The deputy chief had fair reason to consider placing me in Tehran station. First, my special

program had kept my cover clean: I had no visible affiliation with the US Government, much less with the Agency or any of

its usual cover providers. I did have military service--eight years of active duty with the US Marine Corps. But between those

years and my entry on duty with the Agency I had spent 5 1/2 years as a university student.

The nature of my military experience and education probably also helped prompt DC/NE to look at me for assignment to

Tehran. During my eight years of Marine Corps service, I had first been an air traffic controller and, for more than half

my service time, a designated Naval Flight Officer flying as a weapons system officer in high-performance jets. When my time

for a tour in Vietnam rolled around, I was assigned to a fighter/attack squadron deployed aboard an aircraft carrier. I flew

76 missions over North Vietnam, South Vietnam, and Laos in the venerable F-4 Phantom. While no hero (indeed, I was the most

junior and least experienced aviator in the squadron), I nonetheless had been subjected to the pressures of potential life-and-death

situations and to high standards of performance. On returning to school, I earned a Ph.D. in Government, specializing in Executive-Congressional

relations and Constitutional law associated with American foreign policy. This background seemed to nudge DC/NE toward selecting

me for Tehran, and later it also was to serve me well in critical ways, in circumstances the nature of which I could have

scarcely conceived.

Soon after my conversation with the DC/NE, however, I was told that the Tehran assignment was being withdrawn. When the

acting chief of station (COS) was offered an inexperienced first-tour officer, he not unwisely rejected me. His position,

which is difficult to rebut, was that Tehran was a hostile environment in which contacts and agents were placing their lives

at risk by meeting in discreet circumstances with American Embassy officers (all of whom, of course, were considered by many

Iranians to be CIA). Therefore, our Iranian assets deserved to be handled by experienced officers who knew what to do and

how to do it. Further, any compromise whatsoever, for any reason, would unquestionably have severe repercussions for US-Iranian

relations, which the Carter administration was trying to resurrect. Hence I was offered another station as an alternative.

It was sometime in late June or early July, while I was on the other country desk, that I was again offered Tehran. A

permanent COS had finally arrived in Tehran and, when my candidacy was raised with him, he did not hesitate to say yes. Later,

he told me that given a choice between a well-trained, aggressive, and smart first-tour officer or a more experienced but

reluctantly assigned officer who would rather have been somewhere else, he would take the first-tour officer. I thought then,

and have thought ever since, that the COS made a courageous decision--one that, had I been in his place, I might have decided

differently. He earned my respect right then and there, and it has never waned.

I accepted quickly. Shortly afterward, elated at the thought of going to a very-high-visibility post of great significance

to policymakers, I was on the desk reading in. When the day came to depart for Tehran, I called on DC/NE. He ushered me into

his office, chatted a minute or two about my itinerary, wished me well, and, shaking my hand, looked at me and said, "Don't

[expletive] up." I wish he had been able to convey that message to a few other government officials downtown.

Historical Perspective

Iran (then known as Persia) at the turn of the century was a barren country barely existing

as a grouping of tribal fiefdoms, more or less caught in the rivalry between Russia and Britain. The discovery of oil in Persia

in 1908 changed things considerably for the Persian people and the two competing empires, particularly the British, but had

little initial impact on US interests. With the events in revolutionary Russia in 1916 and 1917, that nation's ability to

exercise power and influence in Persia diminished, and Persia quickly became fully incorporated into Britain's sphere of influence.

Succeeding US presidents avoided any official contact or involvement, preferring instead to sidestep Persian entreaties and

to recognize that the country was now within the British sphere.

In 1925 a Persian Army officer, Reza Pahlavi, became something of a national hero by halting a Communist-sponsored revolt

in northern Persia. He parlayed that success into being elected Shah by the civilian Parliament, and then turned that semidemocratic

position into a highly autocratic dictatorship. In short, he became just the latest in a centuries-long line of Persian masters

who ruled by fiat and fear.

Officially calling his country Iran, Reza Shah began a reign that left him popular with virtually no one. Before World

War II, he engaged in modernization of his country, although not necessarily for benevolent or public-spirited motives (one

of many reasons he was detested by his subjects). During his reign, Iranian-US relations continued at a low ebb, with neither

country understanding the other's culture and with much distrust existing on both sides.

It took World War II to create the Iranian-US ties that were eventually to become so seemingly invincible and permanent.

The Soviet Union had been invaded by the Nazis in June 1941 with three field armies, one of which headed for the Transcaucasus

region in southwestern Russia. With vital lines of transport and communication severed, there remained only two avenues of

supply by which needed US lend-lease and other materials could reach the Soviets: the always dangerous Murmansk Run for ship

convoys, and the Trans-Iranian Railroad reaching from the warm-water ports of the Persian Gulf to the Soviet borders in northwestern

Iran. The Transcaucasus thrust also threatened Iranian oil fields, for which Germany's need was desperate.

The outcome was the occupation of Iran in the north by Soviet troops and in the south by predominantly British forces.

Reza Shah (whose army was completely undistinguished in its efforts to deter the arrival of foreign troops) was forced into

exile on the island of Mauritius, and his teenage son, Muhammad Reza Pahlavi, was placed on the throne in a figurehead status.

During this period, both Soviet and British troops earned Iranian antipathy as occupiers who were, in the eyes of most Iranians,

looting their country while fighting a war in which Iran had no stake. (This enmity was not without some justification, although

the British were never given the credit they deserved for significant and measurable assistance to the Iranian people throughout

this period.) All of this, of course, deepened Iranian suspicions of foreigners and hostility toward outsiders who tried to

or, in this instance, actually did control the country. The US Government's stake in Iran, as well as its diplomatic and military

presence, concomitantly increased as a consequence of America's unyielding support to its wartime allies, Britain and the

Soviet Union.

With the war over in 1945, the Soviets refused to leave Iran, as previously agreed to under a 1943 treaty. Instead, relying

on sympathizers in the local populace they had worked to cultivate during the war, the Soviets commenced a blatant attempt

to annex the northern regions of Iran, coveting both the oil and access to a warm-water port. By the time American and British

troops had departed from Iran in spring 1946, the Soviets were firmly ensconced in the province of Azerbaijan and were moving

into Iran's Kurdish region.

Although George Kennan was still a year away from enshrining the geopolitical strategy of containment in his celebrated

"Mr. X" article, the highest officials in the US Government had already recognized the true nature of Stalin's Soviet Union

and the need to prevent, where possible and practical, the USSR's expansion beyond its own borders. Exerting strong diplomatic

efforts, including mobilization of the nascent UN General Assembly, the US Government finally succeeded in getting the Soviets

out of Iran and in having their puppet governments in Azerbaijan and Kurdistan disbanded.

Now, with Soviet and British influence over Iran greatly diminished, US-Iranian relations on all fronts gradually expanded,

with the first arms sale by the United States to the Iranian military coming in June 1947. From then on, oil and "strategic

imperatives" cemented and drove this unnatural relationship, despite continuing and increasing distrust and antipathy toward

each other over the next decades.

CIA involvement in the overthrow of Prime Minister Mohammed Mossadeq in 1953 loomed extraordinarily large in the minds

of Iranians. In April 1951 the then-popular but eccentric Mossadeq, a wealthy career civil servant and uncompromising nationalist,

had been appointed by the Shah as prime minister to replace his assassinated predecessor. Shortly thereafter, the Shah, under

pressure from Iran's political center and left, signed an order nationalizing the British-dominated, putatively "jointly owned"

Anglo-Iranian Oil Company (AIOC); Mossadeq had earlier submitted, and the Majlis (parliament) had approved, legislation mandating

AIOC's nationalization. The ultranationalist Mossadeq, who had advocated remaining aloof from both the Soviets and the Americans

(rather than continuing the usual strategy of embracing both in order to play one off against the other), soon came to be

seen by many in the West, including Washington, as de facto pro-Soviet.

The nationalization of AIOC touched off two years of political turmoil, during which Mossadeq's popular support eroded.

This period culminated in August 1953 with the Shah's flight into a brief exile, CIA's stage-management (under explicit Presidential

directive) of the coup against the Prime Minister, and the Shah's return (with US Government assistance) and consolidation

of his power. Subsequently the United States, driven by the inexorable forces of the Cold War, increasingly assumed the role

of chief protector for Iran and the Shah, leaving many Iranians more convinced than ever that the Shah and their country were

simply a dominion of the United States, administered by or through the CIA. The seeds of the Iranian revolution of 1978-79

were being sown.

Fifty-Three Days

I arrived in Tehran on 12 September 1979 and began the first of what turned out to be only 53

days of actual operational work. If I knew little about Iran, I knew even less about Iranians. My entire exposure to Iran,

beyond the evening television news and a three-week area studies course at the State Department, consisted of what I had picked

up during five weeks on the desk reading operational files.

Virtually all my insights into Persian minds and personalities came from a lengthy memo written by the recently reassigned

political counselor, which described in detail (the accuracy of which I would have ample time to confirm) how Iranians viewed

the world, and why and how they thought and believed as they did. It did not take much to see that even friendly and pro-Western

Iranians could be difficult to deal or reason with, or to otherwise comprehend. The ability displayed by many Iranians to

simultaneously avow antithetical beliefs or positions was just one of their quainter character traits.

One memorable introduction to all this was my first encounter with the Iranian elite several weeks after my arrival.

In this instance, I met with an upper-class Iranian woman who was partnered with her husband in a successful construction

company. This couple was wealthy and held degrees from European and American universities. They were well traveled. But, her

exposure to the West and level of education notwithstanding, this woman insisted that the Iranian Government was directly

controlled by the CIA. She said that the chief of the Iranian desk at CIA Headquarters talked every day to the Shah by telephone

to give the monarch his instructions for that particular day, and that the US Government had made a deliberate decision to

rid Iran of the Shah. Since the US Government did not, in her scenario, have any idea whom it wanted to replace the Shah as

ruler, it had decided to install Khomeini as the temporary puppet until the CIA selected a new Shah. I was both fascinated

and stupefied by this explanation of the Shah's downfall.

The woman's unshakable theory did not encompass an explanation of why the United States would have permitted the bloody

street riots in 1977 and 1978. Nor did it explain why, if the US Government (or the CIA) wanted the Shah to leave, he was

not just ordered to go, thereby avoiding the enormous problems of revolutionary Iran.

My initial weeks in Tehran passed quickly. The Chargé, L. Bruce Laingen, was more than helpful, as was Maj. Gen. Phillip

Gast, US Air Force, head of the MAAG, with both of them generously taking care to include me as a participant in substantive

meetings at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs (MFA) and Iranian General Staff Headquarters. I worked essentially full-time during

the day on cover duties, which I found much more interesting than onerous, dealing with issues of genuine import; in the evenings,

I reverted to my true persona as a CIA case officer. I was 32 years old, at the top of my form both physically and mentally.

Captivity was to change all that, and I have never since regained that same degree of mental acuity and agility. But during

those 53 days on the streets of Tehran, I reveled in it all.

On 21 October, however, I came to realize that my euphoria would probably be short-lived. On that date, the other station

case officer (as acting COS) shared a cable with me in which CIA Headquarters advised that the President had decided that

day to admit the Shah, by then fatally ill with cancer, into the United States for medical treatment. I could not believe

what I was reading. The Shah had left Iran in mid-January 1979 and had since led a peripatetic life; indeed, he had even rejected

an offer of comfortable exile in America (to the relief of many US Government officials). Now, with US-Iranian relations still

unstable and with an intense distrust of the United States permeating the new Iranian "revolutionary" government, the Shah

and his doctors had decided the United States was the only place where he could find the medical care he needed.

The Shah Comes to America

Since February 1979, strong pressure on President Carter for the Shah to be admitted

to the United States had been openly and unrelentingly applied by powerful people inside and outside the US Government, particularly

by National Security Adviser Zbigniew Brzezinski and banking magnate David Rockefeller, with added support from former Secretary

of State Henry Kissinger. Had the Shah come directly to the United States when he left Iran in January 1979, there probably

would have been little or no problem--the Iranians themselves expected this to happen and were surprised when it did not.

But, as the ousted monarch continued to roam the world, the US Government was also working to build a productive relationship

with the new revolutionary regime. Thus, as a practical working plan, the greater the American distance from the Shah, the

better for the new relationship--and vice versa. The Shah's entry into the United States 10 months later, however, quickly

unraveled all that had been achieved and rendered impossible all that might have been accomplished in the future.

When the Shah's doctors contacted the US Government on 20 October 1979 and requested that he be admitted immediately

into the United States for emergency medical treatment, the President quickly convened a gathering of the National Security

Council principals to decide the issue. Only Secretary of State Vance opposed the request; the others either strongly supported

it or acquiesced. The CIA was represented by DDCI Frank Carlucci in the absence of DCI Stansfield Turner; it is instructive

to note that Carlucci was not asked for CIA's assessment of the situation. The meeting concluded with President Carter, while

harboring significant misgivings about letting the Shah in, nonetheless acceding to the majority vote and granting permission

for the Shah to enter the United States for "humanitarian" reasons. The President, familiar with warnings from Bruce Laingen

about the danger to the Embassy if the Shah were to be admitted to the United States, asked what the advisers would recommend

when the revolutionaries took the Embassy staff hostage. No one responded.

Hundreds of thousands of Iranians were enraged by the decision to admit the Shah, seeing in him a despot who was anything

but an adherent to humanitarian principles. They also felt, not for the first time, a strong sense of betrayal by the US President.

Disillusionment

In 1976, Jimmy Carter had campaigned for the presidency on a platform that included a strongly

stated position advocating human rights around the world. Friendly or allied nations exhibiting poor adherence to those criteria

were not to be excluded from sanctions, one of which was the withholding of US military/security support and related assistance.

Many Iranians heard this and took heart, believing that President Carter would cease US support to the Shah's government while

also easing, or stopping completely, the abuses taking place in their country.

On 31 December 1977, while the President was making a state visit to Iran, he openly referred to the country as an "island