|

The picture below is of an American Listening station. The Soviet Union had several missile launch sites, and stations lke

this provided the means to reord the electronic telemetry the Soviet ICBM's sent to their controlling stations. These stations

in Iran gave the United States tremendous knowlege of the arsenal in the Soviet Union.

Click on this link to go to the original web site of this article.

The united States supported a coup in Iran in November of 1952 to August of 1953. Our CIA was totally involved with maintaining

an unpopular leader in order to have someone we could be sure would support the United States politically against the Soviet

Union. This was the one chance for Iran to be truly a democratic style nation, but instead we Supported the Shah of Iran.

I do not think the Shah was a bad choice, and many wonder if the election was legitimate. Either way, we chose someone

who had a better desire to see the people of Iran grow internationally instead of becoming a puppet government of the old

Soviet Union.

That was a great fear back then. The Soviets gaining control of a Persian Gulf country and their oil would have been

a disaster for the United States and the free world.

The Central Intelligence Agency's secret history of its covert operation to overthrow Iran's government in 1953 offers

an inside look at how the agency stumbled into success, despite a series of mishaps that derailed its original plans.

Written in 1954 by one of the coup's chief planners, the history details how United States and British officials plotted

the military coup that returned the shah of Iran to power and toppled Iran's elected prime minister, an ardent nationalist.

The document shows that:

Britain, fearful of Iran's plans to nationalize its oil industry, came up with

the idea for the coup in 1952 and pressed the United States to mount a joint operation to remove the prime minister.

The C.I.A. and S.I.S., the British intelligence service, handpicked Gen. Fazlollah Zahedi to succeed Prime Minister

Mohammed Mossadegh and covertly funneled $5 million to General Zahedi's regime two days after the coup prevailed.

Iranians

working for the C.I.A. and posing as Communists harassed religious leaders and staged the bombing of one cleric's home in

a campaign to turn the country's Islamic religious community against Mossadegh's government.

The shah's cowardice

nearly killed the C.I.A. operation. Fearful of risking his throne, the Shah repeatedly refused to sign C.I.A.-written royal

decrees to change the government. The agency arranged for the shah's twin sister, Princess Ashraf Pahlevi, and Gen. H. Norman

Schwarzkopf, the father of the Desert Storm commander, to act as intermediaries to try to keep him from wilting under pressure.

He still fled the country just before the coup succeeded.

Mohammed Reza Pahlavi was the shah of Iran from 1941 to 1979, except for a brief period in 1953 when Prime Minister Muhammed

Mosaddeq overthrew him. Mosaddeq was in turn overthrown with assistance from the U.S.,and the shah was returned to power as

a U.S. ally. He greatly modernized Iran and established social reforms, many of which angered fundamentalist religious leaders.

In 1979 the religious opposition, lead by Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, drove the shah into exile. Khomeini sought the capture

of the shah, and when it was learned that he had been admitted into the

United States for medical treatment, Iran's response

was the start of the hostage crisis at the U.S. embassy in Teheran. After dismissal from the hospital the Shah fled to Panama,

then Egypt. He died on July 27, 1980, at the age of 60.

Shah Reza Pahlavi ruled Iran until 1979. The Shah used

his oil wealth to modernize his nation, as Attaturk had done in Turkey. The Shah’s “White Revolution” allowed women to vote

and hold jobs, built big cities, and created a more secular or non-religious society.

Iran had been a very devout

Muslim nation, and many Iranians were very unhappy with the Shah’s changes. Further, many people close to the Shah were corrupt.

Anyone who disagreed with the Shah was forced to leave the nation or face SAVAK, the Shah's brutal secret police force

In January 1979, the Iranian people revolted and forced the Shah to flee. A popular religious leader, the Ayatollah Ruhollah

Khomeini gained of the nation control and created an Islamic republic. The Ayatollah denounced the United States as the “Great

Satan”. Shortly after the United States

allowed the Shah to come to New York City for cancer treatment, Iranian students

stormed the American embassy and held 52 Americans hostage for more than a year. Iran released the hostages in 1981, but tensions

continue to exist between the United States and Iran, two nations with

very different cultures.

Khomeini was

born in a small village near Tehran. He followed his father into theological studies. In 1964 he was banished by the Shah.

In early 1979 he returned to Iran after the Shah was forced out of the country. With popular support, Khomeini became the

leader of the country and set

about creating a fundamentalist Islamic theocracy. Khomeini encouraged partisans to seize

the U.S. embassy culminating in the Iranian hostage crisis. He also help start a war with neighboring Iraq which lasted eight

years. He ruled Iran until his death in 1989 .

Many people of the Middle East want to return to a fundamentalist

Islamic society.

The forced rapid changes of recent years made some people uncomfortable. Some people feel a western-like

society makes it harder for Muslims to "submit to god." Many Muslims feel that western values are decadent. Mullahs,

Islamic holy men, are prominent in the region, and their declining influence is a concern to many people. Religious leaders

changed many aspects of life in Iran after they took control in 1979.

Boys and girls attended separate classes.

Students entering Iranian universities had to pass a test on the Muslim faith. Alcohol and western music were forbidden. Men

could not wear T-shirts, short sleeved shirts, or neckties. Women and girls had to wear long, dark garments that covered their

hair and body. Anyone suspected of opposing the revolution was severely punished.

http://www.iranian.com/Jan96/History/EagleLion.html

Who knew what was happening in the months leading to and after

the 1979 revolution? Everybody had their own theory -- and still do. Including the Americans, who were supposed to know more

than anyone else.

Secret American documents published after the takeover of the United States embassy in Tehran

in November 1979 contain a wealth of first-hand day-to-day accounts and analyses. These documents, which would normally have

been declassified decades from now, have been obtained by the New York Public Library for all to see.

Here are three

examples of those documents, which give an indication of what was going through the heads of American diplomats and analysts.

The first is by John Washburn, whose official position has not been mentioned in the document. In fact, at the end of the

document, written in September 1978, there is this handwrittten question: "Who is he?"

According to one

Iranian who had met Washburn in Tehran at diplomatic parties, he used to be a member of the diplomatic staff at the U.S. embassy

in the early 70's. He was fluent in Persian and used to call himself "Yahya Beshour-o-besouz" which is a literal,

but also clever, translation of his name.

The second document is from a political officer at the U.S. consulate

in Shiraz written in September 1978. The third is a letter by Bruce Laingen , the U.S. Chargé d'Affaires in Tehran, written

to his family on November 1, 1979 -- three days before the takeover of the U.S. embassy.

SECRET/NOFORN

September 18, 1978

Dear George,

Thank you for including

me in the September 7 meeting. As promised, here are comments on issues raised there.

Iranian Character - Alternate

Leaders

------------------------------------

At the meeting, a number of conclusions were drawn on the basis

of sweeping assumptions about the Iranian character and its unchangeability. There are, it is true, well- known negative characteristics,

in the Iranian personality such as cynicism, self- consciousness, and archaic individualism which are personally and socially

negative.

These have been described over and over again by commentators on Iran, and more catalogued in [Marvin]

Zonis' book, The Political Elite of Iran. (I hope that sometime soon you will be able to read the last chapter of this book

-- only 11 pages -- if you have not already.)

Some of the speakers in the meeting seemed to think that the only

effect of these characteristics is to strengthen the Shah. However, that is only part of the story, the importance of which

is rapidly ebbing.

Iranians have always been intensely and unashamedly aware of these defects and now resent the

way in which the Shah's method of rule reinforce them.

It is a cliche of both standard academic literature on politics

in Iran (Bill, Zonis, Cottam, Binder, Jacobs), and of the common conversation of Iranians themselves, that the Shah's system

of control and governance uses and depends on the failings in the Iranian characters, thereby strengthening them. The Shah

himself admits as much in Mission for My Country.

This way of governing associates the Shah in the minds of Iranians

with what they most dislike in themselves, continually generating profound and continuing resentment against him. It has done

much to prevent him from being accepted (as he yearns to be by his people) as the supreme nationalist.

Furthermore,

many Iranians believe that the same defects on which the Shah capitalizes politically also seriously retard economic development,

education, social responsibility, and the growth of modern consciousness.

Their awareness of these vices, and the

way in which the Shah plays on them, continually builds up a sense among aware Iranians that the Shah's regime anomalously

seeks forced- draft economic modernization through profoundly reactionary governing methods which endanger the country's future

politically and as a society.

This feeling is particularly strong among those groups -- businessmen, professionals,

which could provide alternative leaders. The conventional wisdom is that such leaders are not to be found because those who

might become leaders are co-opted or otherwise neutralized by the Shah's carefully playing on the Iranian personality. This

is only partly true.

Iran has the normal (small) proportion that any nation may expect of brave, socially conscious

and responsible men. Some of these men have found ways to live, and live reasonably well in Iran, outside but closely observant

of the governing process, without losing their self-respect and sense of integrity.

There are also those, who,

out of religious, political or professional principle, or for other reasons have openly opposed the Shah, such as the signatories

of the Charter of 32, in actions which require considerable courage whatever the motives for them may be.

After

the Shah, What?

------------------------------------

Another feeling which underlines the current opposition

is that the Shah's time in history was a real and important one for Iran -- which is now over. In this perspective, his system

of government, which was necessary and important in pulling a fragmented people together and preserving their independence,

now is seen as an obstacle to Iran's aspirations and the future development of all the important

aspects of its national

life.

This may seem obvious and academic, but it has a double importance. First, it is a main source of the Iranian

sense of impermanence about the Shah's regime which several people at the meeting noted -- the feeling that the Shah "will

not last my life time."

Second is the sense among a great many Iranians of all classes that there is nothing

in their government except the Shah. This in turn comes from the perception that not only has he not established any structure

of government which can survive a transition, but also that the monarchy as he conceives it, will not be acceptable to most

Iranians when he goes, nor will any other authoritarian government which tries to rule in this style.

(This is one

reason why I do not think a purely military takeover in succession to the Shah has much chance of stability or longetivity.)

This is why, in addition to the clear and pressing issues of human rights and rational development in Iran, continuing

liberalization is so important to many Iranians and to us. The right kind of liberalization can make a start on a permanent

framework for Iranian political life, and on some experience in using it.

Otherwise, whoever succeeds the Shah will

have to reorganize Iranian politics and government from ground up, and to do it in the center of a whirlwind of domestic fears

and unleashed emotions, and of outside pressures.

Sh'ism (sic)

------------------------------------

The meeting may have left the impression that Sh'ism and Shiite clergy are innately and totally reactionary. In fact,

Sh'ism's formal indifferences to politics make it possible for its devoted followers to support many different forms of government.

Sh'ism is inheritently (sic) nationalistic since it represents the adoption of Islam to the Iranians' desire to

have a religion of their own not dominated by the Arabs. Furthermore, Sh'ism has a greater potential for adaptation and accommodation

to new circumstances and governments than Sunnism because it holds that the Gate of Interpretation is still open, whereas

Sh'ism in theory forbids theological

interpretations not found in the Koran or the teachings of the Prophet.

The Shah's repression of religion in Iran has made Sh'ism's predominant groups dogmatic and conservative in the course of

defending themselves, just as Roman Catholicism has become in Communist countries. Even so, I see Sh'ism as conservative socially,

but with an inherent anti-authoritarian bias politically.

For this reason, in an Iran in which there is freedom

of religion and religious organization and practice, and freedom to express religious convictions politically, I would expect

that, as in Turkey and Israel, there would be one party devoted to conservative religious positions, particularly on social

issues, and a number of other parties across the political spectrum to which devoted persons would belong without much sense

of violating their religious beliefs or being opposed by their religious leaders.

Next Steps

------------------------------------

The consequences of what has been described in this letter are that Iran is a country with very considerable economic

development which is acutely underdeveloped politically. Iranians are totally and painfully aware of this.

This

means that we have only two realistic possibilities to choose between. These are the turbulence of a country dynamically trying

to work out its own permanent form of government, or the turbulence of a people struggling with regimes which do not understand

or consciously reject the process of trial and error in achieving a lasting polity.

If the Shah can bring himself

to tolerate turbulence in the search for permanent structure of government and the emergence of such a government which would

have real power of its own, two things he has never been able to do in the past, then progress can begin while it is still

in power.

Accordingly, [President] Carter's emphasis on continued liberalization in his recent telephone call to

the Shah was right on target. We must consistently press for liberalization with the Shah so that Iranians, seeing this, will

at least give some credence to the idea that we

mean it and that we will be similarly insistent with future regimes.

If the Shah really does proceed with free elections, political parties, a freer Majles, and a freedom of political

expression, he will begin to secure his country from its almost total political underdevelopment and hope of a reasonably

stable future after him.

This outcome would make up in some degree for all of our indiscriminate support to the

Shah in the past, and offer Iran the best long-term chance to be a viable nation able and willing to play the role we hope

for it in the Middle East.

Unfortunately, however, intermittent repression is much more likely, making it quite

possible that the Shah will be removed in the next decade by assassination, coup, or irrestible (sic) population pressure.

The best possible future government for us in these circumstances would be one dominated by an alliance between civilians

and younger military officers.

The worst would be a regime dominated by senior military officers. This is, however,

the one we may be most likely to get initially, although I think there is a possibility of a move directly to civilian government

which would have a good chance of success.

Iranians to keep reactionary generals in power. Above all a very great

majority of Iranians regard such a regime certain to be much worse than the Shah's. It is therefore critically important that

we are never seen as encouraging such a regime, no matter in what straits the Shah finds himself, or what chaos initially

succeeds him.

In the meantime, we must use the present episode, even if the Shah weathers it, to get it firmly established

among ourselves that our need to know and understand Iran's internal political developments now permanently outweighs any

damage we may do to the Shah, or to our relations with him, by being seen to be making our own independent assessment of those

politics.

Indeed, his awareness that we are doing this may well add weight to our encouragement of continued liberalization.

At the same time, our identification with the Shah, particularly through such public events as arms sales and public statements

should be discreetly but constantly cut back as far as it is consistent with our not being perceived as simply abandoning

him.

Finally, it may be that some of the following actions have not yet begun. If so, I think that they should be

started immediately:

A. Top priority must be given in both the [U.S.] Embassy and CIA to reporting on internal events

and domestic politics in Iran. You know what is needed here far better than I, and we both know the excruciating difficulties

of doing this.

It may be worth noting that the consulates should be given the mandate and resources necessary to

get fully involved in this. Access is much easier outside of Tehran and many of the significant activities are going on where

the consulates are.

B. There should be regular and systematic consultation with the academic community. Many academics

have been calling the shots on Iranian politics much more accurately than we have. There are many unused resources here to

use them, and these men and women should know that the advice is needed and wanted.

This consultation, which should

deeply involve ICA, should also include regular monitoring of publications. The materials so covered ought to include PhD

theses. Many on Iranian matters noted in the American Political Science Association Journal appear to cover in depth matters

on which we are particularly ignorant.

The Middle East Institute should be regularly tapped for its resources to

Iranian studies. The American Institute for Iranian Studies based at the University of Pennsylvania and which apparently has

been almost ignored by us is a very important resource.

Academics who have worked in Iran on other disciplines,

such as at Harvard's Iranian Center for Management Studies, should also be regularly conferred with.

C. Either through

academics or directly, discreet contact should be established with Iranian exiles and their organizations in the US. For example,

what do we know about the newly-established Committee for Human Rights in Iran which is apparently the American arm of the

Charter of 32 group?

D. [Department of] Commerce should be asked to assist in contacts with American businessmen,

many of whom are remarkably perceptive and who frequently have unusual access.

I would be glad to talk over with

you how these consultations might be organized. It will not be easy to overcome suspicion of us among private American groups

interested in Iran, especially academics.

This has been a long letter. I hope it is useful. Please use it in any

way that you wish.Please also let me know whenever there is any other way I can be helpful. Good Luck!

Sincerely,

John Washburn

Click here to hear a Jimmy Carter Speech

CARTER, JIMMY

1924- , thirty-ninth president of the United States. When Carter took the oath of office in 1977,

he inherited a nation divided by the social turmoil of the 1960s and disillusioned by the cynical political practices

of the Nixon White House. Within minutes after his inauguration, Carter left his heavily armored limousine and,holding

hands with his wife, Rosalyn, walked the parade route to the cheers of spectators. Carter's stroll down Pennsylvania Avenue

seemed to symbolize the end of one era and the beginning of another. In retrospect, however, the Democratic victory in 1976

was a historical anomaly in an era of Republican domination of the presidency.

Carter, the son of a Georgia landowner

and businessman, was part of the first generation of moderate southern politicians who emerged in the aftermath of the civil

rights movement. His term as Georgia governor (1971-1975) was a modest success, marked by an emphasis upon governmental reorganization

and aggressive actions to end racial discrimination. Still, it hardly seemed a springboard to the White House, and his announcement

in December 1975 that he would seek the presidency evoked incredulity or amusement from most knowledgeable political observers.

But they underestimated Carter. American voters were disgusted by the Watergate revelations of corruption, and they

responded warmly to the soft-spoken southerner with his perpetual smile and his often repeated promise: "I'll never lie

to you." His moderate economic views, his commitment to civil rights, and his background as a southerner helped him assemble

a coalition of traditional Democrats, blacks, and southern whites who had become increasingly alienated from the Democratic

party. Carter narrowly defeated incumbent

Gerald Ford with 50.1 percent of the vote.

Carter's administration

was not without achievements. The drive and focused intelligence that carried him to the White House made it possible for

him to push through (by one vote) the Panama Canal Treaty in 1978 and to broker a peace agreement between Israel's Menachem

Begin and Egypt's Anwar Sadat in the fall of 1978.

But failures in domestic and foreign policy overshadowed these

accomplishments. He had been elected as an outsider, and he often proved inept in dealing with his own party. He also seemed

unable to mobilize public support for his policies of restraint and sacrifice.

He was dogged, too, by events beyond

his control: the energy crisis that triggered double-digit inflation, the fall of the shah and the seizure of hostages in

Iran, and the chill in Soviet-American relations following the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan. In retrospect, many of the

crises Carter confronted were insoluble, but his style of hands-on management led a restive American public to hold him personally

responsible for failure. The seizure of American hostages proved his final undoing. Americans' increasing frustration over

the nation's inability to effect their release focused upon Carter. When an attempted rescue ended in ignominious failure

in 1980, his fate as president was sealed. He went down to a smashing defeat at the hands of Ronald Reagan.

n 1986

Carter founded the Carter Center of Emory University, an institution devoted to mediating international conflict and ameliorating

health problems in the world's developing nations. In a departure from the usual quiet retirement of presidents, Carter has

played an active role in numerous diplomatic and domestic efforts after leaving office. In this, he is especially known for

his successful international mediations in countries such as North Korea and Haiti. Jimmy Carter, Keeping Faith: Memoirs of

a President (1982); Erwin C. Hargrove, Jimmy Carter as President: Leadership and the Politics of the Public Good (1988).

AIRGRAM

Classification: Confidential

Message reference No.: A-23

To: Department of State

Info: AMCONSULS

Isfahan and Tabriz (via internal pouch)

From: AMCONSUL Shiraz Date: 9/23/78

Drafted by: Political Officer

Victor L. Tomseth

Subject: Political attitudes in southern Iran

SUMMARY AND INTRODUCTION: Recent conversations

with a variety of people in southern Iran have revealed considerable unanimity as regards [to] dislike for the regime headed

by the Shah but little unity on other issues including the place of Islam.

The discontent is undoubtedly profound,

but aside from students of the radical left who advocate overthrow of the Shah and establishment of a republic, few people

can agree on a constructive alternative to the government as it has been practiced for the last 15 years.

Calls

for early elections free from manipulation are heard fairly frequently. However, thoughtful Iranians, even those whose dislike

for the present regime is intense concede that in the absence of constraints on who can run and under what conditions, elections

are likely to produce a Majles whose members will be incapable of uniting on any issue other than their grievances with the

past government.

Under such circumstances, it seems inevitable that despite lack of enthusiasm for his leadership,

the Shah willcontinue as Iran's ultimate political arbitrator. END SUMMARY AND INTRODUCTION.

It has been extremely

difficult to find anyone in southern Iran with a good word for the Shah in recent days. Iran's population profile gives some

indication why.

Almost half of all Iranians have been born since 1963, the last time the country faced an economic

or political crisis of significance. Almost two thirds have been born since 1953, the last time an alternative to the Shah's

rule was a serious possibility.

Few people among this group are impressed with comparisons of then and now, comparisons

that have profound meaning for someone who has seen Iran transformed from a poverty-stricken country whose sovereignty was

ignored by the great powers to one of the world's wealthier and more influential nations and who played a key role in that

transformation. The post-1953 generation has been

promised the millennium and its comparisons are made by that standard.

Even those old enough to remember the old days of 1953 and earlier have their grievances with the regime. These

range from the secularization of the state to the arrogance of high government officials to the collapse of the real estate

market to corruption to continuing (and often growing) inequities in Iranian society.

The Shah and his advisors

have not been unaware of sources of discontent such as those enumerated above, and have usually reacted to them.

However, sometimes actions taken to alleviate pressures building in one area (e.g., controls on real estate speculation designed

to curtail the number of overnight millionaires and close the gap between rich and poor) have created new pockets of unhappiness

(i.e., among land owners, not all of whom by any means count their holdings in numbers of villages, who hoped to sell their

properties for enough

money to send their children off to college or for a retirement nest egg).

Other times,

the determination to modernize Iran has led to decisions (e.g., giving women the vote) which were known would be opposed (i.e.,

by religious conservatives).

Change always poses a threat to vested interests, but it does not follow that the changes

the Shah has wrought in Iran were foreordained to produce a degree of opposition to his rule which is now so manifest among

the Iranian populace.

Rather it would appear that the manner in which these changes were effected has often been

a more fundamental factor in the reaction to them than the changes themselves. Iranians seem overwhelming to resent having

been excluded from virtually all political decisions of the last 15 years.

As one middle-aged Iranian, who says

he remembers what it was like during Mossadeq's time, put it, "It bothered me less that the government decided to impose

exit tax on Iranians leaving the country than it did to have (former Minister of Information Darioush) Homayoun announce the

decision without going to the trouble of consulting the Majles whose members in accordance with the constitutions are supposed

to represent the interests in government."

Another, a businessman, referring to government interference in

the hours shops can be open, said: "We Persians for the most part retain a 'hand-to-mouth mentality,' the heritage of

the time when Iran was still a poor country. Small shopkeepers are thus inclined to

maintain hours convenient to housewives

whose habits are conditioned by the memory of a former day when they might not have known at noon when buying bread for lunch

where the money would come from to buy the ingredients for dinner.

"In practice, we may not work more than

the forty-hour week common in the West, but we do not like to be told by Harvard-educated bureaucrats who think they know

better than we what is best for us [and] how and when to work it."

Aside form their commonly shared unhappiness

with their government, however, Iranians in southern Iran are deeply divided on most other issues. Rural people, for example,

while they may be deeply religious, are generally uninterested in the agitation for the return of

Ayatollah Khomeini

which has taken place in many urban areas.

They are inclined to view the issue as irrelevant to their major concerns

-- the weather, the availability of water, the price of wheat, etc. Recent arrivals from the countryside in cities where religious

agitation has taken place, on the other hand and notwithstanding the attitudes of their rural relatives, have often figured

prominently in such activities.

The explanation for this seeming contradiction appears to lie in the trauma they

experience in trying to adjust to urban life. Frequently, their religion is the only institution familiar to them in their

new surroundings, and they are thus highly susceptible to the religious emotionalism that surrounds a cause such as Khomeini's.

The business community, too, is divided on the religious issue. The more fervent among its members have willingly

closed their shops in protest against the government and in mourning for fallen martyrs, often at great financial loss.

Others have usually closed as well, but often more in fear of retaliation for not closing than in sympathy for the causes

espoused by the ulema. They may take their religion seriously and dislike the regime every bit as much as the fanatics, but

they are also concerned about their businesses and they resent the disruptions frequent closures bring.

Contempt

for the Islamic fundamentalists is perhaps even more profound than opposition to the regime among many members of the modernist

element of society in southern Iran.

An Ahvaz banker characterized those who had participated in religious demonstrations

(and numerous bank trashings) in that city as "illiterate Arabs who had taken leave of their senses under the influence

of religious leaders hardly less ignorant than themselves."

A senior military officer in Shiraz described the

clergy in general as the worst of Iranian society, lazy louts who entered religious schools for no more noble reason than

to avoid conscription.

An American-trained engineer at Shiraz's Iran Electronics Industries in comparing Reza Shah

(whom he admires) to Ataturk concluded that the latter was a greater leader because he had gotten rid of all of Turkey's ulema

whereas Reza Shah had made the mistake of leaving some alive. His mastery of historical fact might have been shaky, but he

left no doubt where he stood on the religious issue.

Lack of unanimity on the place of Islam is paralleled on secular

political issues as well. Aside from those who have demanded the Shah's ouster and the establishment of a republic (a view

which still seems to be confined to relatively small minorities on the extreme left and right in southern Iran), few Iranians

seem to have considered alternatives to the kind of leadership he has provided.

Critiques are usually limited to

where he has failed with little consideration given to how past deficiencies might be rectified. There does seem to be a consensus

that the present Majles and all those who have served in governments during the past 15 years are discredited. Accordingly,

early elections free from government manipulation are frequently advocated.

Thoughtful Iranians, however, recognize

that there is as yet little of the discipline required for orderly elections present in their country. Most of the parties

and political groupings which have emerged in recent weeks are held together by no more reliable glue than the personalities

of their leaders.

Under the circumstances, these Iranians concede that elections without limitations on who can

run and the size of parties which can field candidates are likely to produce a Majles whose membership would be an assemblage

of mini-parties incapable of uniting on any issue other than the inadequacy of past governments, hardly a viable alternative

to the Shah.

In sum, Iran is confronted with a difficult dilemma. Many Iranians, if southern Iran can be taken as

representative of the rest of the country, are dissatisfied with the character of the leadership they want in its place.

Further, short of violent revolution and the imposition of a regime which in all likelihood would be every bit as autocratic

as the Shah's, the Iranian people do not appear at this time to possess the self-discipline to find a way out of their predicament.

Thus, it seems that by default, the Shah will continue as the ultimate arbitrator of Iran's political future.

Tomseth.

Tehran, Iran

Nov 1, 1979

Dear Folks,

Well this has been another one of these special sort of days in

Iran... a day that had us worried but that turned out not so bad after all.

It was Eid-e-Gorban, an Islamic holiday

celebrating the feast of sacrifice. And being such, there was a large sermon and prayer meeting scheduled here and in most

of the cities of Iran. Well enough, but the day also concluded with a growing surge of government and clerical stimulated

criticism of the U.S. for our admission of the Shah for medical treatment in New York.

And so, the Eid celebrations

also became a day to mount a strong public agitation against us. Here in Tehran it had been announced that after the big rally

in the south of the city the crowd would move in procession to the U.S. Embassy where speeches against us would be delivered

and where slogans would be mounted.

So we were prepared for up to a million demonstrators in the streets around

the Embassy. That meant getting all non-essential personnel off the compound, the marines concentrated inside the Chancery

to protect it, and those of us who were needed inside the Chancery -- among other reasons to destroy records and comm equipment

if we were again invaded and to keep in touch with Washington by phone

and cable ... And also to keep in touch with the

local government authorities to be sure that we had some kind of protection from them. The marines of course were in battle

dress and eager to defend the place...

But all of that proved unnecessary in the end, happily. Late last evening

it was announced on the radio that the procession would not go all the way to the Embassy, but that instead it would go to

a square about a mile or so south of here where the speeches against us would be heard and the slogans adopted. The reason

being that the distance was far; it was Eid holiday and time was needed for prayers and visits with families.

Nevertheless

we stuck to our contingency plans, and by 0900 we had our demonstrators, but much fewer in numbers. The group, possibly organized

by the Communist party here, started at about 50 and eventually grew to about 4,000....

Their tactics seemed to

be to keep us off balance and worried all day, since they stuck with us until about four in the afternoon, marching back and

forth around our compound, chanting slogans and shaking their fists against us all the while. (We've decided that for the

next week anyone who shows up at the consulate and asks for a visa with a sore throat will be rejected on the spot!)

The crowd included a lot of women in Chadors and even some children in trollers. At no time did they try to come over

the walls but they did manage to spray a lot more graffiti on our walls... We had enough as it was from previous demonstrations!

We kept in touch with worried Washington by telephone and stuck it out. The only real trouble developed late in

the afternoon as the thing was winding up... One of our security officers decided to take down a large cloth banner that had

been put up on the large iron grill gates at the Embassy's ceremonial entrance...

The banner said something derogatory

about Carter and praised Komeini... Well, some of the last of the crowd saw what was happening and didn't like it at all...

In fact the crowd got very angry and got the Iranian police (about 45-50 were guarding the embassy today, unarmed, and had

been pretty good about keeping the crowd moving...) to join them (!) in demanding that the banner be put back on the gate...

We said OK, provided it was hung somewhere else.

Nothing doing, said they, and if we didn't cooperate they were

coming over the walls. Well by that time we decided we would not stand on our pride if it meant turning the police against

us. So the banner went back up (much to the disgust of our marines) and there was another hour of angry slogans against us...

but no violence...

That was it, except for a brief flurry this evening when large crowds leaving a sports stadium

nearby paraded past us, yelling more angry slogans. Again we retreated to the chancery, but it proved brief, over in about

15 minutes.

You probably wonder what triggered all of this, though I suspect you know. Guess I mentioned it above...

the Shah. There is mounting irritation over this and we are in for some trouble if the Shah stays on for further treatment

on an out-patient basis.

We have emphasized, at the highest levels here short of the Ayatollah, that our admission

of the Shah was entirely on a humanitarian basis; we regard him without any political authority in Iran; we deal with the

present government; we respect and support Iran's independence and territorial integrity; we have reminded the Shah's party

that he cannot engage in political activity while in the U.S., etc., etc.

But that has not satisfied either the

government or the press, which sees some other purpose on our part in what we have done; regards the Shah as the basest of

criminals and wants him here for trial.

Where this will all end is unclear at the present but we are going to have

some heavy weather for a while I fear, especially if he remains in the U.S. for extended treatment. Pity, because up to now

we had been making some progress, however slowly, in getting confidence here, in what is a real uphill struggle.

But not everything has been trouble... We've tried to continue reasonably normal lives when we can. The [diplomatic] Community

has organized a volleyball league ("Laingen's Invitational Volleyball Series"); we've lost tennis matches to both

the Italian and the British

Embassies, and we've had a splendid Halloween dance, the latter organized by the young people

of the [US Embassy] Defense Attache Office.

The weather cooperated, as we could put tables out on the terraces and

we were able to have something more than 250 people for a magnificent dinner prepared by our amazing Italian cook and dancing

again until three in the morning. They organized dance concerts... disco, waltz, polka, and slow... and a great time was had

by all.

In fact, we are becoming celebrated in the diplomatic community for the parties at this embassy. Never

fear, we are discreet too. The Residence is far enough from the the street so that we do not disturb the Islamic fundamentalists...

A few Iranians come, but mainly it is

the diplomatica and private community... all of which are frankly starved for such

"taghooti" (corrupt) entertainment because none of it is available in the city... Although there is a rumour going

around that there is dancing occasionally at the roof restaurant of the Sheraton

Hotel...

There are a good

number of hotels here but most of them have about 10-20% occupancy, given the total absence of tourists. And some of the hotels

have been taken over by students this past week, grumbling about the absence of dormitory space... This poor government! It

has so many problems on its hands and it is very reluctant to offend the students who after all had so much to do with the

overthrow of the Shah.

Nothing further has developed on the question of the assignment of an ambassador here...

Again the time is a bit inappropriate, given the ruckus over the Shah... So I don't know where things stand at the moment...

I was asked recently to take an assignment as Consul General in Jerusalem, but I have asked to be removed from

consideration for that job... It seems very peripheral to the main activity in the Middle East, what with our Embassies in

Tel Aviv, Cairo, and Amman very much in the act, not to mention all the other players like Straus and all the other cast of

characters...

It would have been a comfortable place to live perhaps, but not all that good for school for Jim,

a prime consideration affecting wherever we go next in this transient life that is the Foreign Service of the United States...

Love, Bruce

PS: We called on a leading mullah at the senate building last week -- an interesting conversation

with a man deeply suspicious of us but apparently prepared to listen, recognizing that Iran has problems not dealing with

us.

But perhaps the most interesting part of the call was the 12-14 year old girl who saw our black Chrysler limousine

waiting outside and who asked my security officer, "Who's car is this?" When told it was the American Charge she

said, "... but I thought all the Americans had left... We're going to chase them out!" She's not representative,

but what she said says something about the impact of some of the propaganda heard in much of the press -- propaganda that

some of its proponents genuinely mean and which others express for effect.

Author

"http://humwww.ucsc.edu/History/historyjournal/edbernhardt.html

"Richard

J. Thomas"

Cyrus Vance and the Iran Hostage Crisis

The Iran hostage crisis tested the will of all the

American diplomats directly involved with the conflict. Cyrus

Vance was the Secretary of State at the beginning of the

crisis and spent most of his final six months in office trying to negotiate with an elusive Iranian bureaucracy. As the

diplomatic efforts and patience ofCyrus Vance became a political liability, domestic pressure began to build for the Carter

administration. Eventually Vance's policy and efforts directly led to the hostages release, but not without a price. Cyrus

Vance directed the Carter Administration's efforts in creating policy during part of the crisis. But when did his opinion

cease to have influence over Carter? Also,why did the men differ so completely on the hostage rescue issue? To fully understand

answers to these questions some context must be created. The two aspects that require background are the Carter administration's

foreign policy apparatus and the hostage crisis. In the Carter Administration, Secretary of State Vance played the role of

co-policy maker with President Carter. President Carter wanted Vance to be a collaborator, not a designer of foreign policy(McLellan

28).Secretary of State Vance's function was as the diplomat transacting the nations business abroad. Carter wanted to alone

set priorities, control direction, and make final decisions on foreign policy matters. The Administration was set up so that

Vance would be the veteran (Washington insider) diplomatwhile Zbigniew Brezinski would serve as the concept man.

Both "Zbig" and Cyrus were to inform Carter andexpress their differing views on diplomacy. This system left the

Presidentto make the final decisions(Kaufman 37). The collegiality system left Vancewith no direct control over policy, only

influence over the President. Between November 4th, 1979 and January 20th, 1981 the UnitedStates policy towards Iran was centered

on the hostages. Sixty three

Americanswere taken hostage in the US embassy in Tehran while three more hostageswere taken

at the Foreign Ministry(Vance 375). The hostage takers weremilitant students. The Iranian government was falling apart under

the revolution'sweight and so had no control over the angry mob. This left the Carter administrationin a confusing position

because the political dynamic in Tehran was a strangeone.

The hope within the White House was that the hostages would

be releasedin a few hours as soon as the government got involved. This had happenedon February 4th in 1979, hut the political

dynamic had changed. Vance andthe Department of State were bewildered as to who to contact to free thehostages(Vance 375).

As it became clearthat Khomeini possessed the most power in Iran, the United States triedto open communications with

him. This was a fruitless effort because Khomeinigained popularity in part do to his anti-American stance. The Carter Administration

believed that the hostages were valuable only if left unharmed becausethey were being used as pawns in a power struggle(Vance

377). For the firsttwo months Cyrus and the Department of State completely dominated the decisionmaking process on the crisis(Sick

238). With Vance's advice Carter decidedearly on in the crisis to pursue two main goals. The first being the protectionof

national honor and interest, the other being the safe release of thehostages. In obtaining these two ends the administration

set aside certainactions that would not be taken. They were that the Shah would not be returnedto Iran, the US would offer

no apology for past American policy or actions,and that the US would not allow hostages to be tried for treason(Vance377).

To do this a the administrationfollowed a "dual track strategy(Vance 377)." The first part was that allpossible

links of communication would be used to contact the hostage keepers.This contact would help the US determine the health of

the hostages andthe motives of the students. The second strategic aspect was political,legal, and economic pressure imposed

on Iran by international bodies. TheCarter administration was attempting to isolate Iran from the rest of theworld in order

to create outside pressures for the

hostages release(Vance377- 378).

This method of dealing withthe hostage

crisis was clearly in the Vance conflict management style.Jerel Rosati wrote that "Vance believed passionately in the

pursuit ofglobal peace and cooperation through the use of diplomacy...(ll2)." Hewas a proponent of quiet diplomacy and

he urged Carter to go in that direction.To set this slow diplomatic tone Vance told reporters that early in thecrisis quiet

and firm diplomacy was required(Kaufman 160).

On November 28th a meetingtook place at White House situation room

involving the top officials entangledin the hostage crisis, except the President(Sick 235). This meeting wasa turning point

in the US strategy. The National Security Adviser,Zbigniew Brezinski, was concerned that Carter was locking himself intoa

mode of diplomatic inaction. But, Brezinski could not prove that militaryaction

would strengthen America's position or

free the hostages(Sick 237).As Brezinski pushed for acceleration of the administrations actions Vancedisagreed. To Vance the

question was not what could be done for the sake of escalation, but, rather what could be done to

improve the situation(Sick236).

Vance's position again won favor in this meeting. His strategy fromthe beginning was one of diplomacy and the subordination

of military ideasto the diplomatic process(Sick 238).

The success of the quietdiplomacy presented by Vance came early

on in the hostage crisis. One ofthe first communication links was through the PLO and this connection immediatelypaid off.

On November 17th the negotiators for the PLO got thirteen hostagesreleased from the embassy(Vance 378). This release of hostages

coupledwith Carter's show of strength boosted his domestic standing and he enjoyeda record gain in approval during this time.

"According to a Gallup poll, in the four weeks since the hostageshad been seized, public approval of Carter's

presidency jumped from 30percent to 61 percent(Kaufman 160)." But, other diplomatic channels hadnot been fruitful and

as domestic pressure began to push Carter, Carterbegan to question Cyrus's policy.

With the Soviet invasionof Afghanistan

the world view that Vance espoused was no longer ascendantin the White House(Rosati 112). Vance wrote that the late December

invasionby the Soviets was a severe set back for the policy he favored. In hisbook Cyrus wrote that after Afghanistan "the

tenuous balance between visceralanti-Sovietism and an attempt to regulate dangerous competition could nolonger be contained(Vance

394)." In Gary Sick's book All Fall Down, hepointed out that Vance seemed visibly hurt by the invasion. Also, thatthe

Soviet invasion marked the end of Cyrus's policies within the Carteradministration(292).

A simple division in time

providing a moment whenVance's influence ceased to be important is inaccurate. Vance was stillclearly involved in policy decisions

for the rest of his stay in office. There is a clearer point in the Iran hostage crisis when Vance was ignored, if not purposely

leftout of the decision process. This event was the failed hostage rescue attempt.From the very beginning of the crisis Carter

had asked Zbig to keep the military option open.

Burton Kaufman noted that "When the hostages were first taken a

military strike was considered impractical. The US simply lacked the military ability to rescue the hostages(l60)." Vance

believedthat any rescue attempt was not only counter productive but dangerous.Throughout the conflict Secretary of State Vance

expressed his extreme skepticism about any rescue mission being successful(Rosati 112). But,by April of 1980 all other essential

officials felt considerable pressure to take action. This fact later became clear in their memoirs(Dumbrell171).

After all of the most recent efforts at a diplomatic solution to the crisis failed, a meeting was calledby Carter. At Camp

David on March 22, 1980 Carter and his advisers discussedthe issue of a hostage rescue mission. Again, Vance voiced his opposition

to any use of force

including mining ports or even a blockade. Vance believed that the situation inside Iran would make

negotiations possible. He also stated that as time past the likelihood of physical danger for the hostages diminished. The

only use of force justifiable to Vance was in reactionto a hostage being harmed(McLellan 159).

This was not the

advice Carter desired. Carter knew that his reelection depended on a stroke of genius. His possible reelection looked impossible

unless Carter could rid himself of his appearance as an indecisive, helpless leader(McLellan 159).Carter had fallen out of

favor with the American public since the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan. His public approval rating was falling and Americans

began to indicate a desire for change in leadership. On March 25th in the New York State Democratic primary Edward Kennedy

beat Carter 59 percent to 41 percent(Dumbrell 171).

With these facts looming over the Carter administration it is

no wonder there was sense of urgency.But, Vance was attempting to keep the hostage issue away from national politics. McLellan

writes that "Brezinski reported that in the three weeks after the March 22nd meeting a decision crystallized, with Vance

kept inthe dark, to go forward with the rescue mission(l59)." The finalizing meeting detailing

the rescue mission

was held on April 11th. This meeting conveniently took place while Vance was in Florida enjoying a long weekend with his wife(Sick

292).

At this meeting Warren Christopher sat in on behalf of Vance.On the subject of a rescue mission Christopher

knew nothing. He made the assumption that Vance must have known about the plan and approved it otherwise he would not have

taken the weekend off(Salinger 235). After the April 11th meeting Carter's mind was made up; a military rescue attempt was

assured.The meeting only took an hour and Carter ordered the mission to continuewithout delay(Sick 292).

Upon Vance's

return to Washington,Deputy Secretary of State Warren Christopher informed Vance about the meeting.Vance was angry; early

in the morning on April 14th Vance went to the WhiteHouse to voice his opposition to any rescue attempt. Carter told Vance

that it was the hardest decision he had made since becoming President.The argument Vance made that morning was compelling

enough to cause Carterto call a meeting of the National Security Council(Vance 409- 410).

At the Tuesday meeting ofthe

NSC Vance laid out why he fundamentally disagreed with the hostage rescue mission. He first pointed out that a functioning

government was now in place and able to negotiate on the hostage issue. Also, Vance said that the hostages were in no immediate

danger and in satisfactory health.Vance brought up the point that even if the hostage rescue was successful there were plenty

more Americans in Tehran to take hostage. On top of those ideas Vance stated his even larger fear of an Islamic-Western war.

The last idea expressed by Vance in the NSC meeting was that he feared a military operation of any kind might push the

Iranians to the Soviet's side(Vance410). Vance was ignored and the mission went ahead depending on a naive faith in technology

and no proper rehearsal(Dumbrell 172).

On April 21st Vance handed Carter his letter of resignation in which he stated

he would resign whether the rescue mission was a success or failure. The mission was not a successand it cost eight men their

lives. Vance was proven to be justified in his sincere fears about the rescue mission, but he was not pleased. Carter and

Vance were close friends and it hurt Vance to leave Carter in a time of need. But, it was time for Vance to move on and let

the administration to deal with its latest crisis(Vance 411). ; Carter made an irrational choice when he ordered a hostage

rescue attempt. Carter's illogical decision was made under extreme pressure and urgency. The rescue mission caused Vance and

Carter to have a unreconcilable split in foreign policy ideals.In Carter's time in office he had lost the willingness to suffer

through public setbacks in order to follow a straight diplomatic course. It is hard to blame Carter for adjusting his stance

on Iran. At the beginning of the crisis it was easy to be diplomatic. Public opinion was sweeping his way as the lucky thirteen

came home. But, as diplomatic efforts faltered and Carter's popularity dropped he rightfully felt some urgency to look strong.

; By March, Vance had already leaked his resignation at the end of Carter's term. This coupled with thefact that the post

Vance held was not one as an elected official. As an appointed official Vance felt less domestic pressure. ; I admire Vance

for his courage to stand up for his beliefs and his willingness to giveup his position in protest. But, it was clearly easier

for Vance to make a stand for his ideals

then for Carter to remain strong against devastating public opinion polls. Carter

allowed domestic pressure to effect his thinking on an international issue. This caused him to make a poor decision. Vance

took the liberty to look at the Iran hostage crisis without allowing domestic influences to effect his analysis. For this

Vance deserves respect.

; A lesson begging to be extracted from this information is that domestic stress can cause those

in elected authority to make unhealthy foreign policy decisions. Carter became a victim of this pressure and it helped to

undo his Presidency. For Vance's efforts,he received praise for his ability to stand by his principles. I am sure that one

of his greatest moments as a diplomat came as he debriefed the

hostages in Germany. He explained to them every effort

that was made to secure their release and he also clearly explained why he resigned. Cyrus Vance was applauded by the hostages

for his efforts to assure their safe return. "The weight of his commitment to a peaceful solution and his concern for

them as human beings struck deeply resonant chords in the majority of the group(Saunders 282)."

Rarely do diplomats

receive applause for their efforts, in this case Vance deserved it.

comments to edberhar@cats.ucsc.edu

EddieBernhardt

Bibliography

Barber, James David. The Pulse of Politics. New York: W.W.Norton andCompany,

1980.

Dumbrell, John. The Carter Presidency. New York: Manchester UniversityPress, 1993.

Kaufman, Burton

I. The Presidency of James Earl Carter, Jr. Lawrence,KS.: University Press of Kansas, 1993.

Kissinger, Henry. For

The Record. Boston: Little, Brown and Company,1981.

McLellan, David S. Cyrus Vance. Totowa, NJ. Rowman and Allanheld

Publishers,1985.

Moses, Russell Leigh. Freeing the Hostages. Pittsburgh: University ofPittsburgh Press, 1996.

Rosati, Jerel A. The Carter Administration's Quest for Global Community.Columbia, SC.: University of South Carolina Press,

1987.

Salinger, Pierre. America Held Hostage. Garden City, NY.: Doubledayand Company, inc., 1981.

Saunders,

Harold H. "Beginning of the End." American Hostages in Iran.Ed. Paul H. Kreisberg. New Haven Yale University Press,

1985. 281-296.

Sick, Gary. All Fall Down. New York: Random House, 1985.

Vance, Cyrus. Hard Choices.

New York: Simon and Schuster, 1983.

Appendix

;Cyrus Roberts Vance; was born March 27th, 1917 in Clarksburg,West

Virginia. Graduated from Yale with an A.B. in 1939 and LL.B

in 1942.He served in the navy during WW II from 1942-1947.

Was admitted to thebar in 1947. Vance practiced law in New York from

1947-1961 and again from1969-1976. In the Kennedy

administration he was general council for theDefense Department and secretary

of the army. Under Lyndon B. Johnson Vancewas

deputy secretary of defense. Vance was Secretary of State under PresidentJimmy

Carter from 1977-1980. In 1983 he wrote

his memoirs; Hard Choices.

Feeling, John E. Dictionary of American Diplomatic History. New York:Greenwood Press,

1989.

They actually made stamps of the event. One I will never collect, but this next shot is what they look like.

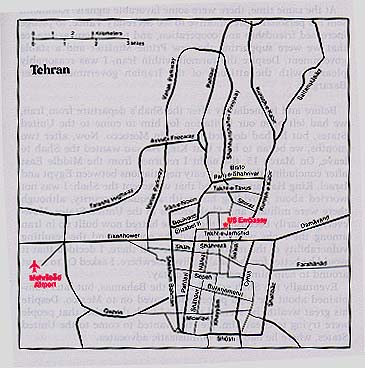

This is a crude map if Tehran, with the Embassy located near the center of the map.

This was an exciting time, historically.

What many forget, is that the Soviet Union invaded Afghanistan in 1979, also. This invasion happened about 1 month after the

embassy was attacked. It created much confusion, for many years the Soviet Union claimed one of their goals was to have a

warm water port that they had access to all year round, and due to geography, there is no warm water port that exits to a

major body of water. Many felt that the invasion of Afghanistan was a prelude to two things: Either a buildup of forces for

an eventual attack on the Persian Gulf oil fields, or, an attempt to later invade southern Iran or Pakistan in an effort to

finally get that warm water port. This next page is photos of the Russian ships that we encountered in the Arabian

Sea. Click on this map for the next page.

|